If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Scribes and Libraries of the Carolingian Court (2) | |||||

| Many of the often quoted statements about Charlemagne and literacy derive from the work of his contemporary biographer, Einhard. This work is known to be defective in such matters as chronological detail, and presents an idealised portrait of the great man in the mode of Classical writers describing a Roman emperor. Nevertheless, certain comments stand out as having a plausible ring, and as the author points out himself, he was there and saw it with his own eyes. |  |

||||

| Portrait of Charlemagne, as drawn by a 17th century antiquarian from a now destroyed ancient mosaic in Rome. He is depicted wearing the Frankish clothing which Einhard claims he always wore. | |||||

| Einhard refers to the emperor's education in the liberal arts, and claims he extended the same privilege to both his sons and daughters. He tells us that Charlemagne spoke Latin fluently, but understood Greek better than he could speak it. This was a time of linguistic development in Europe, with Romance languages which had absorbed Latin from the days of the Roman Empire diverging from the Germanic languages which had not. The Frankish empire encompassed both groups and the use of Latin for legal and diplomatic purposes could be seen as a unifying influence. Spoken Latin may have been a second language for the Germanic speaking Frankish aristocracy. The churches were the guardians and teachers of Latin literacy, so the encouragement of orthodox Latin literacy created a synergy between church and state. | |||||

|

According to Einhard, Charlemagne himself made reforms to how the psalms were chanted and the lessons read, as he was expert at both these exercises, even though he didn't do it in public. This may, perhaps, be personalising a process in which liturgical reform and the standardisation of texts was occurring with the approval and encouragement of the king. It is a similar metaphor to that which says that King Alfred personally translated the Bible and other texts into English. Well, perhaps they did, but I'm sure a few litterati among the clergy helped. | ||||

| A Carolingian church, as depicted in the Utrecht Psalter. | |||||

| Charlemagne gathered learned men about him. Einhard claims that he was taught grammar by Peter the Deacon of Pisa, and in all other subjects was tutored by Alcuin, a deacon from York, and librarian in their famous library, now entirely lost. Alcuin founded the Palace School which was open to the sons of magnates and any youth of talent. Paul the Deacon was another learned figure who was associated with the court. The learned and literate were all churchmen, but those who were closest to the court were not necessarily ecclesiastics of rank. | |||||

| Charlemagne and his learned friends played little literary games among themselves, giving each other nicknames of figures from Classical literature or the Bible. These are listed among the many letters of Alcuin, and Charlemagne himself, which have been collected and recorded. Charlemagne's own nickname was King David, which apart from any reference to his wives and concubines, suggests a model for kingship derived from the Biblical tradition. He modelled himself on a figure not only of splendour and power (and sexual prowess), but of cultivation and learning. |

|

||||

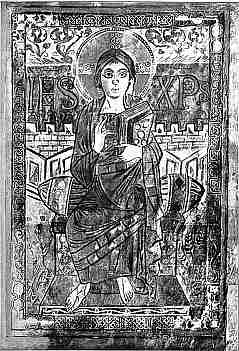

| King David, from an Anglo-Saxon manuscript. | |||||

| The court library of Charlemagne and those of the abbeys patronised by the crown developed together. Instructions were sent to find and gather together old manuscripts for copying. These included liturgical works, necessary for the process of restoring those religious texts which had become corrupt, or which were derived from older Latin versions of the Bible rather than St Jerome's Vulgate. They also comprised works of the Latin Classics, including pagan authors, for the purpose of teaching Latin literacy and the liberal arts. Alcuin himself is credited with producing a revised version of the Bible, and primers in the subjects of orthography, grammar, rhetoric and dialectic; works which still survive through copying. Little known Classical works were ferretted out from forgotten corners of old monastic libraries where they had lain neglected in favour of the books of liturgy and religious commentary which were copied in the pioneering missionary days. |

|

||||

| Image of Alcuin from a 9th century Bible of the school of Tours. The scholar is depicted with a nimbus, like a saint. | |||||

|

The best and brightest from Alcuin's Palace School became abbots and other high ranking clergy in the important abbeys of the kingdom. Books were produced by or under the influence of the court school and donated to the abbeys. Books collected by the abbeys were loaned to the court and other abbey libraries for copying. The king provided patronage for the production of lavish volumes by the abbeys. It is hard to envisage the famous court library of Charlemagne as a separate entity from the developing network of religious institutions. It is easy to see what the abbeys were getting from the king. What the king was getting in return was a stable and literate church full of educated men who could speak and write the one language known across much of western Europe. His barbarian kingdom based on tribal allegiances, redistribution and exchange was developing some trappings of a civilised empire. It didn't last, but the literate church did. | ||||

| The Carolingian abbey of St Riquier, from a 17th century copy of an 11th century manuscript, itself a copy from a 9th century manuscript. | |||||

| Religious centres like Corbie, St Riquier, Lorsch, Metz and others were encouraged as centres of literacy and grew as religious institutions. The literate churchmen contributed not only to the transcription of liturgical and educational works, but to those works which supply the nuts and bolts of historical narrative, the annals and chronicles providing names, dates and places for contemporary events. | |||||

| According to Einhard, it was stipulated in Charlemagne's will that the collection of books in the court library should be sold to whoever wished to buy them, and the proceeds given to the poor. Whether every single volume was dealt with in this way is not known, but the collection and the direct knowledge of its contents vanished. However, it is more than likely that a core of the collection survived to build the new library of his son, Louis the Pious. Bischoff (Bischoff 1994) has undertaken some intricate detective work to attempt to recreate the contents of that library. In addition to a small, dispersed group of surviving manuscript books which have been attributed to the court school, he has identified works which were referred to or quoted from by members of the court school, and followed up leads on works which were copied by associated abbeys during the era. | |||||

|

|

||||

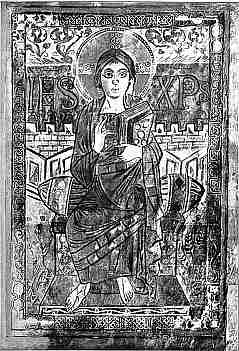

| Miniature pages from two works which have been associated with the court school of Charlemagne. At left, a figure of Christ from the Godesscalc Evangelary (Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. n. acq. lat. 1203, f.3r), at right St Matthew from the Harley Evangelary (British Library, Harley 2788). Both illustrations are in Classical style. | |||||

| While the surviving books are very fancy and lavish volumes of liturgy, treasured for centuries because of their value as objects and art works, the range of works identified by Bischoff by more indirect means includes many works of the Latin Classics, some of them quite obscure and only rediscovered again many centuries after. Bischoff also claims that a list of Latin authors written in an ancient manuscript in the German National Library in Berlin, thought to be a list of manuscripts from the abbey of Corbie, is in fact part of the catalogue of the court library. This analysis largely identifies works rather than specific surviving codices, but is a fascinating piece of paleographical detective work. However, more recently scholars have been questioning the identity of this list, reviving the question of the nature and extent of the court library. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||