|

|

Scribes

and Libraries of the Carolingian Court |

|

The

significance of the king and emperor Charlemagne to the fostering and

preservation of literate Latin culture at a time when it was struggling

back across the landscape of early medieval Europe does not seem to be

in dispute. While Charlemagne's court and chancery

extended written culture beyond the monastic cloisters where it was confined

in much of northern Europe, it was a collaborative endeavour with the

church rather than a separate strand in the history of literacy. |

|

|

The

image of the man as portrayed by the sources of his time is dualistic. The

man of action galloping out to subdue enemy after enemy to expand his realm,

and being portrayed in terms befitting a Roman Emperor until he actually represented

himself as one, contrasts with the pious lover of learning who worked to reform

the practices of the church and revive the literate culture of Classical Rome.

These two aspects combine to produce a pretty powerful image. However, his

legacy in history and legend cannot be put down just to medieval spin doctoring. |

|

|

|

At

left, a Carolingian manuscript depicts mounted soldiers armed with lances

and shields going to war behind a standard bearer (St Gall, Bibl. conventuelle,

ms.22). At right, a 10th century miniature depicts Charlemagne giving counsel

to his son Pepin, king of Italy, while a scribe records proceedings (Modena

Cathedral Archives, Cod. ord. 1. 2., f.156.) |

|

While

many authors have made much of Charlemagne's love of learning and his

desire to reinvigorate literate Classical culture, Christopher De Hamel

paints a picture which places books within the framework of conquest and

redistribution of wealth which allowed the Carolingian realm to exist.

Alliances of fractious noblemen were held together through the redistribution

of conquered lands and booty. The wealth of the kingdom was invested in

treasure. De luxe manuscripts

lavishly decorated with gold could be seen as part of this national treasure,

conferring prestige to their owners, and distributed in exchange for loyalty.

The use of gold in prestigious Carolingian manuscripts has been attributed

to Byzantine influence, apparent also in the painting style of miniatures

and Carolingian architecture, but that does not preclude a social significance

particular to Frankish culture. |

|

|

Lavish

gold decoration on the mosaic ceiling of the ambulatory vault in Charlemagne's

Palatine Chapel at Aachen. |

|

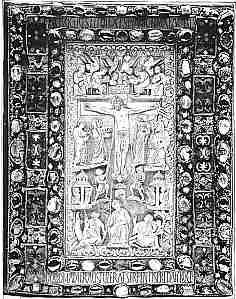

Some

especially lavish manuscript books of the era demonstrate the fondness

for extravagant and expensive decoration in their covers. The example

at left combines the use of precious materials in the form of ivory, gemstones,

enamel and gold with the religious imagery of the crucifixion. The image

projected is that of a reliquary which contains, not sacred bones, but

sacred words. Treasure had its symbolic value in the church as well as

in the world of secular power. |

| Jewelled

and ivory cover of the Metz Evangelary (Bibliothèque Nationale, MS.

Lat. 9383). |

|

The

most expensive and decorative volumes are those most likely to survive

over many centuries, while the more humble books used regularly for religious

practice or scholarly learning are more likely to be worn out or lost.

An assessment of the value placed on literate culture in the Carolingian

court and a reconstruction of the literary works contained and copied

there involves a great deal of historical detective work. Very many works

which owe their survival to copying by court scribes

or by scribes in monasteries with close associations with the court are

now known only from later copies, and in many cases very much later copies. |

|

While

the concept of expensive volumes as booty and bribes fits well with the image

of kingdoms led by belligerent barbarian generals trying to keep their supporters

on side, the greater valuation of literate culture suggests further aspirations.

Carolingian literate culture was also concerned with standardisation and the

reintroduction of order to the practices of church and state. |

|

Charlemagne

had a court library, which was reportedly dispersed at his death. He also

had a chancery producing official documents. The court library and its

scribes evidently worked collaboratively with monastic libraries and scribes.

Outside the court, some survival of Roman law and practice was probably

represented by notaries

and scribes who were continuing the traditions of the past, but the survival

of their output is very limited. Much has to be learned through deductive

methods. |

|

continued

|

Scribes

and Libraries Scribes

and Libraries |

Authors,

Scribes and Libraries Authors,

Scribes and Libraries |

|

|

|

|

|