If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Wills and Inventories | ||

| Wills can be fascinating documents, providing information on social conditions, relations with the church and material culture. There were wills produced in the Anglo-Saxon era in England, and in the Carolingian period on the continent of Europe, but surviving wills only really become common from around the 13th and 14th centuries. | ||

| Medieval Source Material on the Internet: Probate Records provides links to an increasing number of websites with information about medieval wills. Some of these provide full transcripts of the texts of a selection of wills, so you can see what they were like. Fifty Earliest English Wills provides a searchable text of the Early English Text Society publication. If the direct link doesn't work, go to the parent site Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse and type the title into the search box. | ||

| Wills were not used to dispose of the family real estate, as theoretically that was not the legal prerogative of the owner. The legal heir was designated by the crown, and the process could be full of political machinations. Wills were used to make donations to religious bodies such as monasteries, for the benefit of the owner's immortal soul, and to specify the nature of their funerary monument and funerary commemorations. Various bits and pieces of portable property might be apportioned, including clothes, books, jewellery and treasures or household equipment. |

|

|

| This elaborate alabaster tomb in the parish church of West Tanfield in Yorkshire, still bears a metal hearse with prickets for candles. Such arrangements were specified in wills. | ||

| In England wills had to be proved in a church court, and most evidence for them comes from court registers rather than from surviving individual documents. There is a mass of such material, but scattered in repositories all over the place, as there were many centres where such courts operated. They are now found in county record offices, and there are major collections at the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research in York and the National Archives, formerly the Public Record Office in London, where a large collections can now be consulted online. Copies of wills occasionally appear in odd places where they are of interest to the beneficiary, such as cartularies or bishop's registers. Some of this material passed into private hands at the Reformation, and has since found its way back into public collections. What survives is probably only a random fraction of the original material, but still represents a massive data resource for the historian. | ||

|

||

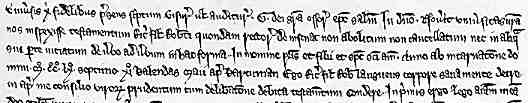

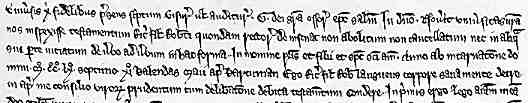

| A few lines from an inspeximus of a will by Geoffrey St Leger, bishop of Ossory, of the will of Richard FitzRobert, late rector of Ennisnag, near Kilkenny (British Library, Egerton Charter 528). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1909) | ||

| This inspeximus, of which a small sample is shown above, represents the will of a clergyman who was also a power in the land. The document is densely written in a neat cursive charter hand and has some of the formal and florid language of a charter, including an address and salutation and an invocation. The testator has specified where his body is to be buried, and specifies donations of money to church institutions as well as family members. The goods which he has specified for disposal to particular individuals include gold and silver cups, garments, a horse and saddlery, and his bedclothes. An inspeximus was a certified copy of a will by an individual whose word could be trusted. The document originally was verified by the seal of the bishop and five others. All this makes the will a significant and formal document. | ||

|

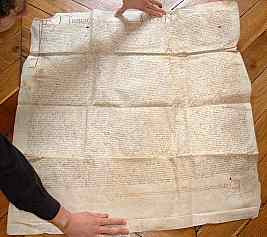

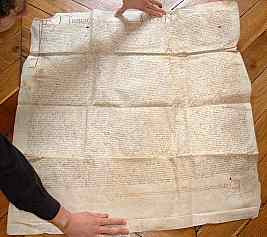

This general view shows the impressive size and detail of a late medieval will. While this example has some rough aspects, such as a rather untidy script and repairs to the parchment, it has some calligraphic flourishes that indicate that it was meant to be an object of significance. | |

| A French will, in the Latin language, of 1474, formerly in the private collection of Rob Schäfer. (All images © Rob Schäfer.) | ||

|

||

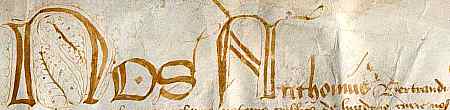

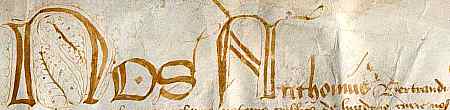

| The heading has elaborate decorated capital letters. | ||

|

||

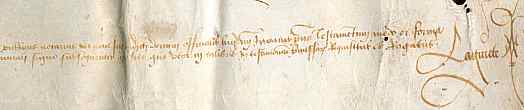

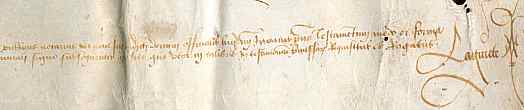

| This will follows the Continental system of authentication by a notary. The words publicus notarius are visible to the incredibly keen eyed at the top left of this section of the endorsement, and the notary's unique mark appears at the right. | ||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||