If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Warrants | ||

| In the centuries after the Norman Conquest in England, written administration steadily proliferated. A single office of the Chancery, issuing documents under the great seal, was not enough to deal with the increasing paperwork, or rather parchmentwork. Various royal secretariats developed, each with their own seal, to deal with different aspects of the work. The first of these, and the one where much work was initiated, was the office of the privy seal which was functioning by the early 14th century. The signet became significant in the late 14th century, later becoming the instrument by which many of the king's actions were initiated. | ||

| There was therefore a chain of authority and communication by which letters were sent from the signet to the privy seal, and from the privy seal to the office of the great seal, ultimately resulting in letters patent being issued under the great seal. This process may have been initiated from within, or may have occurred in response to a petition from a subject. The internal orders passed down the secretariats are referred to as warrants. | ||

|

||

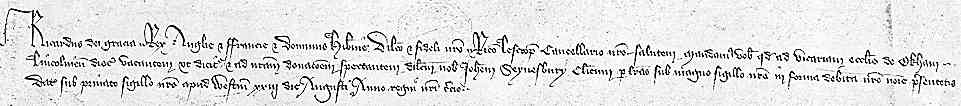

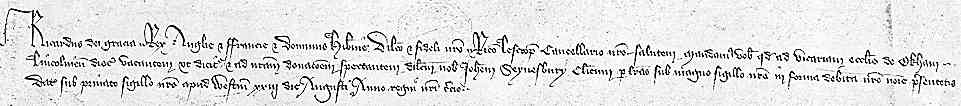

| Warrant of Richard II (National Archives, C.81/461) under the privy seal ordering letters under the great seal appointing John Seynesbury to the vicarage of the church of Okeham. By permission of the National Archives. | ||

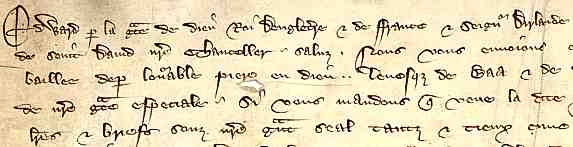

| Warrants are characteristically short and to the point. They are written on a single sheet of parchment which tends to be short and very broad. Consequently they are very difficult to fit on a computer screen. Nevertheless a certain residue of the ceremonious language of more formal documents survives. The king receives the honorifics of his title and there is a salutation to the recipient, in this case the chancellor. The final clause includes the date and the fact that the letter is given under the privy seal. That does not leave much space for the instruction itself, which is about as concise at it can be. The chancellor obviously knew exactly how to perform his part of the proceedings, and only needed the royal nod. | ||

|

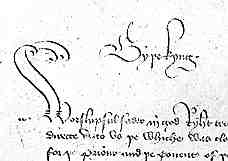

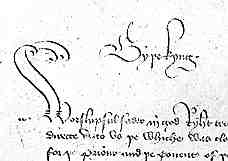

While the form of the document and the script were generally not so formal as public documents like charters or letters patent, the chancery scribes did occasionally get a bit carried away with the calligraphic flourishes. It seems that sometimes, as in the above example, the language was Latin, while in others, as at left, it could be in the vernacular. | |

| The beginning of a warrant under the signet of Henry V (National Archives, AP 9199/184). By permission of the National Archives. | ||

|

||

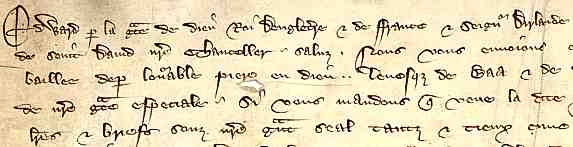

| This is the top left segment of a chancery warrant of 1349, under Edward III, ordering letters and writs under the great seal to the Bishop of Bath and Wells. (London, National Archives C.81/339/20343). By permission of the National Archives. | ||

| The vernacular was not always English. As in the above example, written in a cursive chancery hand, it could be French. While English gradually overtook French as the language of general communication, the latter was still in use in the time of Henry V. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||