If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Private Charters (2) | |||||

|

Charter of 1372, in a private collection. | ||||

| The document illustrated above records a transfer of land between members of the Yorkshire gentry. The seal is missing. While it lacks a salutation, it is addressed in a standard charter format Sciant presentes et futuri (Know in the present and future ...). It has a list of witnesses and is dated. In other words, it has the basic charter format, but lacks some of the elaborations of language and address of a royal charter. | |||||

| As more and more people possessed seals with which to authenticate their charters or other documents, variations in design began to appear. Apart from the equestrian design, heraldic animals or creatures from the bestiary were employed. Sometimes the design forms a rebus, or pun on the owner's name. Such visual puns were also employed in heraldry as everybody and his nephew above a certain stratum of society acquired themselves a coat of arms. A personal seal might in some way reflect their office or position. In the later middle ages, a fancy design with an initial might suffice. | |||||

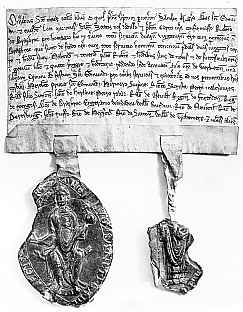

| Seal of Richard de Lucy on a charter of 1153-4 (British Library, Campbell Charters xiv, 24). (From Warner and Ellis 1903) |  |

||||

| Richard de Lucy must have been one of the first on the block with a punning seal. His charter bears a seal with an image of a fish called a pike or luce. | |||||

|

The seal from a 15th century charter, in a private collection. | ||||

| As the charter format was used to do various kinds of business, ecclesiastical bodies became issuers as well as beneficiaries of charters. In fact, some of the historical tales behind the charters become very complex as various claims and counterclaims, deals and counterdeals are carried out using this form of documentation. | |||||

|

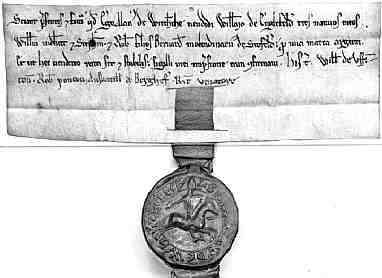

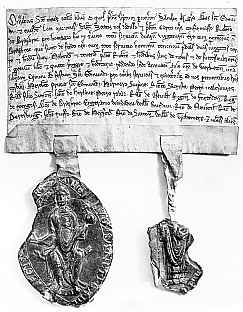

Charter of c.1208-11 of the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds to Robert de Braybroc (British Library, Egerton Charter 2180). By permission of the British Library. | ||||

| This charter of the abbot and convent of Bury St Edmunds, with its hefty and impressive ecclesiastical seals, grants the tenant services of a parcel of land to an individual for his fidelity and service. | |||||

| The charter format was also used by private individuals to ratify agreements that did not involve titles to land tenure. This kind of arrangement could presumably be equally well served by some other from of written agreement, such as an indenture. | |||||

|

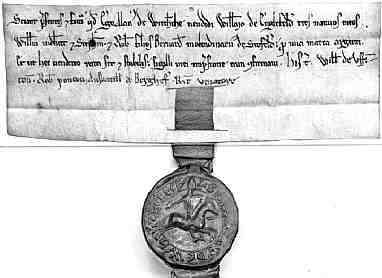

13th century private charter of Alan de Witcherche (British Library, add. charter 20592). By permission of the British Library. | ||||

| The above private charter simply records a transaction. Alan de Witcherche has sold three serfs to Willian de Engelfeld for one silver mark. The seal is of the standard equestrian variety, with a rather more vigorous horse than the previous example. While the historians tell us that serfs were not truly slaves, totally at the mercy of their masters, and had certain rights and conditions guaranteed by law, they could be sold. The charter above is not a title deed to land, but a title deed to people. It is not a grant of privilege, but a record of a business deal. | |||||

| In the earlier days of the royal charter or writ, the document when displayed with the enormous great seal attached and read, no doubt in resounding tones, with all its superfluous language, must have been part of a truly theatrical performance. In later times the words recorded on the many charters acquired a greater significance in law and the documents themselves became more important than the performance of reading them. As the actual documents became more essential to the conduct of affairs, they perhaps inspired a little less awe. | |||||

|

|

|||||

| |

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||