If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Poetry | |||

| Anybody who is around the same age as me probably has a similar experience of poetry. It came in neat anthology volumes which we all read at school. The authors were nearly all dead. It had to be read very carefully and analysed for umpteen layers of meaning. After we escaped from school, we didn't have much to do with poets, who seem to live in little enclaves of society where they publish modest editions in their garages and read their works to each other. The rest of us get our verbal entertainment by playing our pop or folk records and listening to popular songs on the radio. But just a minute, isn't that ........ some sort of poetry? | |||

| In the medieval written word, poetry was not a special isolated category. Verse formats were used in a whole range of written literature, from short pieces to long works, in volumes designed for reading and works created for public performance. This has much to do with the origins of many written forms in oral culture. Rhyme, metre and alliteration can all be used as aids to memory. The oral performer was the precursor to the scribe in areas as diverse as storytelling, theatrical performance and the law. |

|

||

| Oral performance of poetry also included music. | |||

| Many works of medieval poetry are available on the web as well as in printed editions. Check some of the sources on the Medieval Literature links pages of this website. | |||

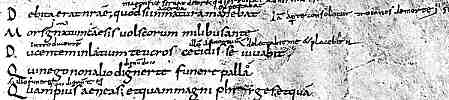

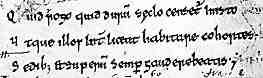

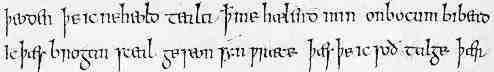

| Poetic works from the Latin Classics were part of the early corpus of literature in the monasteries from which Christian literate culture spread across Europe. Pagan works were studied for the better understanding of Latin literary forms. The mode of presenting these works on the page was carried through various forms of medieval poetry in later days. The first letter of each line was written enlarged and slightly separated from the rest of the line. | |||

|

|||

| A few lines from a 9th century copy of Virgil, showing the enlarged and separated capital letters at the beginning of each line (Bern, Stadtbibliothek, Ms. 165, f.192). (From Steffens 1929) | |||

|

Traditions of vernacular poetry in storytelling mode are recorded through their occasional recording on manuscript, often many centuries after they started doing the rounds of oral tradition. Viking sagas, ballads, or folkloric stories incorporated into written romances must represent a mere fragment of the oral vernacular poetry that once existed. | ||

| A Viking ship, perhaps used by a saga hero? | |||

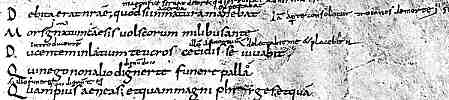

| Vernacular poetry, when eventually written down, was drawn into the service of Christian teaching. The one surviving, and burnt, written version of the epic poem Beowulf incorporates Christian imagery. The collection of Anglo-Saxon poetry known as The Exeter Book specifically addresses Christian themes. | |||

|

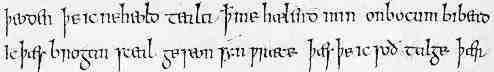

|||

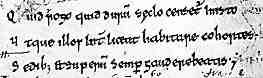

| A couple of random lines from a poem on the Ascension in The Exeter Book (Exeter, Chapter Library No. 3501, f.19b). (From The New Paleographical Society 1903) | |||

| The language in the above example is Old English and the script is insular minuscule. No, it doesn't mean an awful lot to me either! | |||

| For a detailed look at, and exposition of, the content of one of the poems in The Exeter Book, and a peek at images of the pages, check out the splendid website of The Wanderer. | |||

| Religious material of a spiritual or didactic nature could be written in the poetic mode. The priestly writers were familiar with the oral performance of the divine office, and perhaps had a mental template of remembering through oral performance. Yes, I am speculating here, but did Bede expect his Verses on the Day of Judgment to be read silently in a monastic cell, or declaimed in the refectory? Surviving monastic refectories from later centuries contain pulpits for readings at meals, and St Benedict was certainly in favour of it. I suspect that even monks at the time of Bede remembered better than they read, and the verse form helped them do it. |

|

||

| Pulpit in the refectory of Beaulieu Abbey, Hampshire. | |||

|

A few lines from Bede's Verses on the Day of Judgment (British Library, Cotton Domitianus 1, f.54), by permission of the British Library. | ||

| Bede uses the clerical language of Latin, for the benefit of his fellow litterati. The script of this segment of text is a pointed insular minuscule. | |||

| Vernacular paraphrases of the Bible were produced in verse at various times in the middle ages, although heretical movements, or fear of them, tended to send the authorities periodically scurrying back to the security of their Latin. Vernacular verse versions presumably aided teaching the laity, putting the lessons into forms they could understand and remember. | |||

| In the earlier part of the middle ages in England, even legal formulae could have some poetic qualities. At a time when the proving of rights or custom in law was a process of oral proclamation and witness, rather than relying on records of written testimony, alliteration and metre were used as memory aids for legal terminology. Some of this is recorded in Latin charters from shortly after the Norman Conquest, when Old English terminology appears for the specification of certain rights. Legal terms often appear in alliterative pairs, and the whole thing has a certain rhythm. | |||

| et saca et socne on strande et streame on wudu et felde, tolnes et teames | |||

| et grithbreces et hasocne et forestealles et infangenes thiofes et flemene fernithe | |||

| From a charter of Henry I to Christ Church, Canterbury (British Library, Campbell Charters xxi 6). By permission of the British Library. | |||

| We are getting an image from the earlier part of the middle ages of poetry in literate form in the service of the church, while poetry for the laity was largely an oral experience. This does not really differ from the picture for literacy in general and only emphasises the point that poetic forms were a large part of both written and oral culture. In the later middle ages, as the laity became consumers of the written word, new forms of poetry were produced for their delectation. These had their origins, as well as their parallels, in the oral tradition. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||