If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Petitions | |||

| In the oral culture of Anglo-Saxon England, kings received verbal petitions from their subjects in person on matters with which they were empowered to intervene. Over the centuries the increase in written bureaucracy meant that petitions to the king became one stage in a process of written communication whereby matters under the ultimate jurisdiction of the king were brought to his attention, or at least to the attention of his appropriate officers, and dealt with. As the king was a figure with genuine ultimate legal authority and power, a diversity of matters could be dealt with in this way. |

|

||

| These could include litigious matters where one citizen claimed a grievance against another. They also included church affairs, such as approval of the appointment of parish priests or internal administrative arrangements. Spiritual and temporal power were ultimately codependent. | |||

| By the late middle ages, the petition set off a chain of writing events, which can sometimes be traced through the records. The petition, or bill as it was also called, was usually a concise document, addressed to the king and setting the process in motion. | |||

|

|||

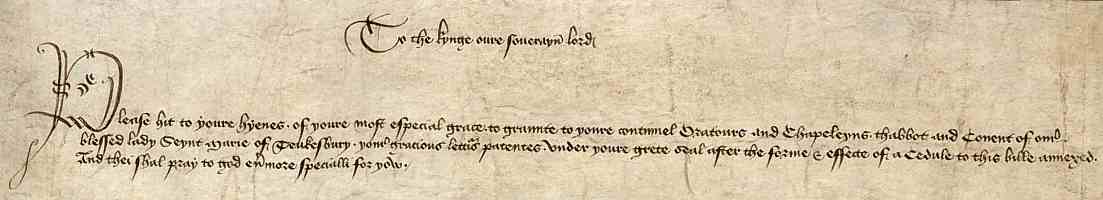

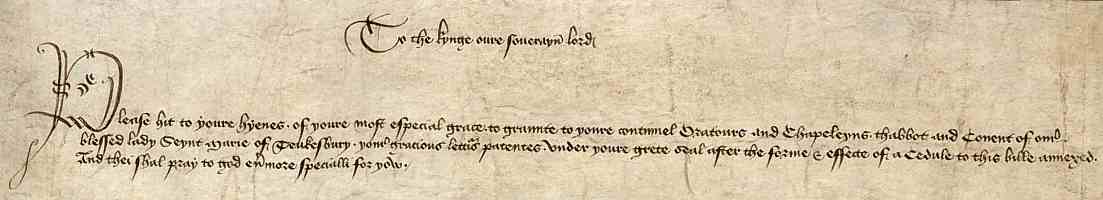

| Petition of 1449 of the abbot and convent of Tewkesbury (National Archives, E.28/79/30). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| The above example shows the concise wording, as well as the long, narrow format which is not unusual. This petition only contains the formalities, with the substance of the matter being included in an attached document. Once received in the chancery, the petition was sometimes annotated with a note indicating what action was taken. This might result in a warrant being issued to another office, such as the privy seal, and eventually a writ or letters patent being issued from the privy seal giving instructions to deal with the matter. | |||

|

|||

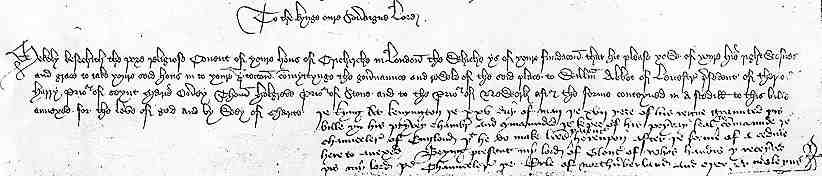

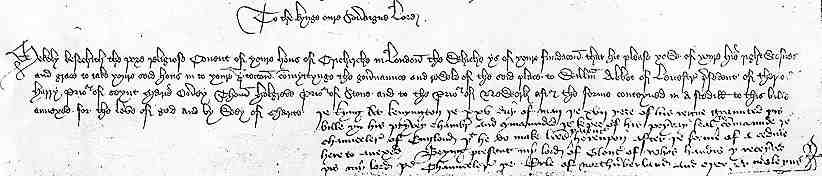

| Petition of 1439 from Christchurch Convent, London (National Archives, E.28/60/38). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| The petition illustrated above has, on the lower right section of the page, the note indicating the action that has been taken. The petition requests changes to the governance of the convent, and the note indicates that the king has approved the production of letters patent to deal with the matter. | |||

| The petition, although a brief document and much less florid in tone than a charter, had certain formalities and niceties of wording. It was addressed formally, but not grandly, to the king. |  |

||

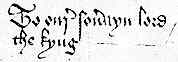

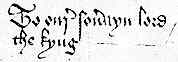

| To our soverayn lord the kyng, from a petition of 1439 (National Archives, E.28/59/57). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| The initial clause tends to a rather grovelling tone, as the petitioner beseeches meekly and sometimes refers to himself as humble or poor. The whole tone really does not go well with modern egalitarianism, but was designed to emphasise the elevated standing of the king and appeal to his mercy, compassion and honourable sense of justice. | |||

| The introduction to the same petition: Besekyth mekly in to your hye and excellent grace. By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| After briefly explaining the matter in hand, the petition might end with a noble sentiment about prevailing justice and truth, or if it was from an ecclesiastical source, with an offer to pray for the soul of the king. A little subtle spiritual bribery was thought to be worth a try. | |||

| The examples shown here are all in English, which would seem to be common by this date, although an august ecclesiastical body might just decide to use Latin for some significant request. The annotations by the chancery clerks appear in either English or French. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||