If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| New Testament Apocrypha | |||

| Not all the stories about the life of Christ, his family and his apostles that were presented by the medieval church are to be found in the regulation books of the New Testament. The relationship beween the stories and depictions that are in the Bible and those that are not are complex and interesting. This relationship has been subject to much simplification, with suggestions that certain books were ferociously excluded by an authoritarian church at a very early stage in its existence, with the idea that these non-Biblical texts were actually banned as heretical, and with the concept that they all represent very early texts that were excluded from the canon. The truth, such as it can be unravelled, is much more complex. These works are known as the New Testament Apocrypha, the very name of which means "hidden", and perfectly respectable books written about them contain such expressions as "secret gospels" in the title. The stories and images were anything but hidden from those who visited churches in the middle ages, as they were part of the imagery of church art and presented in church drama such as the Mystery Plays. | |||

| There is much written about the New Testament Apocrypha. A summary of the history of the texts can be found in W. Schneemelcher (ed.) 1991 (English translation by R. McL. Wislon) New Testament Apocrypha Cambridge: James Clarke and Co., Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press. An interesting recent study on the relationships between the texts and medieval church art is to be found in D.R. Cartlidge and J.K. Elliott 2001 Art and the Christian Apocrypha London and New York: Routledge. Texts and commentary for these works can be found on the web at Early Christian Writings - New Testament Apocrypha or Wesley Centre Online - Noncanonical Literature or Comparative-religion.com - New Testament Apocrypha or The Gnostic Society Library - Christian Apocrypha and Early Christian Literature. Now check that lot out and don't tell me that these are hidden or suppressed texts! | |||

|

Certain iconographic conventions which are recognisable to all of us, such as the depiction of the ox and the ass in scenes of the Nativity of Christ, derive not from texts in the canonical gospels, but from apocryphal descriptions. They are part of our whole conception of the Christian story, and that of medieval folk. | ||

| The Nativity as depicted in 13th century stained glass in Chartres cathedral. | |||

| The texts which make up the rather miscellaneous body called the New Testament Apocrypha are a diverse lot, with varied histories. Somewhere in the second century AD, the Jewish sect that followed the cult of Jesus Christ redefined themselves as an entity with its own official literature. Of the various texts on the life, works and sayings of Christ and his apostles, only certain ones were selected as the official texts of the New Testament. Some of the many texts which were circulating in both oral and written tradition were officially declared heretical, especially if they were connected to the Gnostic theological tradition. Others were simply not included. The entire New Testament canon was not decreed on one occasion. The four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were apparently the accepted texts on the life of Christ by the end of the second century, but it took up to two centuries longer to sort out the precise details of the various accounts of the apostles, the epistles, and the Apocalypse. | |||

|

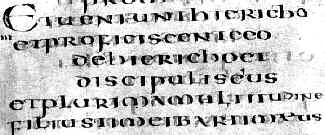

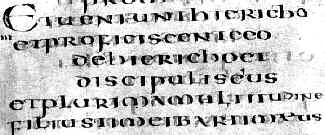

6th century canonical Italian gospel in uncial script (British Library, Harley 1775, f.195). By permission of the British Library. | ||

| The canonical, or New Testament, texts were the only ones which could be used in church liturgy, and had to be preserved unaltered and unembellished, a process which required continual revision against accurate exemplars in the early days. The non-canonical texts were like any other branch of medieval literature; growing, evolving, recombining and acquiring novel additions over the centuries, so that the pedigree of these texts is hugely complex. Early versions have been discovered dotted around both western and eastern Christendom. The stories were absorbed into the writings of the early church fathers, gurgled their way into compilations and were cited in religious commentary. In the 13th century many of the stories, especially those concerning the Virgin Mary and the lives and martyrdoms of the apostles and other early saints, were included in the compilation by a Dominican friar, Jacobus de Voragine, later called The Golden Legend. This work itself acquired accretions and additions in various local versions, and was hugely influential in church art. | |||

|

The problem with the New Testament is that while it contains much in the way of moralising, the actual storytelling is terse and jumpy, with huge gaps in interesting bits of the tale. Our familiar narration of the life and death of Christ is compiled from the various versions in the four gospels, but these have missing bits. The Annunciation, the Visitation, the events surrounding the Nativity and Herod's massacre of the innocents and a couple of quick visits to the temple provide a series of hops to the baptism of Christ and the beginning of the story of his ministry. | ||

| The pregnant Mary meets the pregnant Elizabeth in the Visitation, as depicted in the portal figures of Rheims cathedral. | |||

| A number of texts, often referred to as Infancy Gospels, fill out a range of stories about Christ's infancy and childhood. Miracles galore are attributed to the child, including bringing dead children to life, presaging his future glory. Two early texts of the second century, known as the Protoevangelium of James and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, were reworked and incorporated into later texts, with additonal details. The terse and confusing tale of the visit of the Magi, the vengeance of Herod and the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt has also been provided with considerable circumstantial detail. | |||

|

These stories influenced many depictions in church art, displayed in the centres of worship under the eye of the watchful clergy. The Bible tells us that the Magi visited Jesus at the time of his birth in a stable in Bethlehem. Artistic depictions often show the Magi at the feet of a well grown infant sitting on his mother's knee. This does not represent ignorance of babyhood by medieval artists, but a revision of the story to make a bit more chronological sense in various apocryphal versions. After all, the Magi couldn't catch the Orient Express, and Herod is supposed to have killed all children up to two years old, or older in some apocryphal interpretations. | ||

| Visit of the Magi, as depicted in a 14th century stained glass window in the nave of York Minster. | |||

| These stories were not suppressed by the clergy. In the later middle ages the tale of Salome, the midwife of Mary, who doubted her virginity, conducted a check and had her hand withered as punishment for her doubt, appeared in the Mystery Plays. They have even percolated down into later folkloric tradition, in the guise of such songs as The Cherry Tree Carol, which refers to an apocryphal incident on the flight into Egypt. For a tale which seems to have escaped from even the medieval apocrypha into the wild woods of folklore, give your spine a shiver by listening to Mike Waterson's rendition of Bitter Withy. | |||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||