If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Music (3) | ||

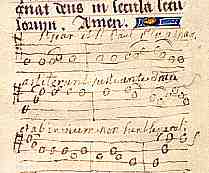

| The system of square notation for church music continued with only minor variations for centuries, and large volumes suitable for reading by a whole choir were produced in manuscript form long after other books were being produced in printed editions, presumably because of the technical difficulty of rendering the music in printed form. An alert colleague pointed out that in the example below, it appears that the square notes and some other symbols have been applied with stamps, suggesting some very primitive technological change in the production of what are still essentially music manuscripts. | ||

|

Segment from a very large gradual leaf, probably of the 16th century, from a private collection. | |

| While one can see that large choir books such as antiphoners or graduals might just have the simple melody and music as sung by the choir, there are also smaller volumes. Processionals were small enough to be carried around by individuals, and possibly some of these smaller works were for the use of the choirmaster, for teaching. The basic format was the same, sometimes with well known passages simply indicated. | ||

|

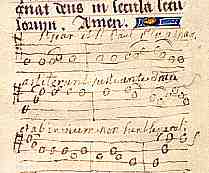

Segment from a small format music manuscript of the 15th or 16th century, from a private collection. | |

| The melody is more fiddly on this example, with occasional bits of polyphony, but the basic system is the same. | ||

| Music that we see in exhibitions of beautiful manuscripts tends to be formally produced for performance and display. The little sample at right shows some informally written music which has been written on the blank parchment at the end of a formal text, a book of hours of the 15th century. The words of the song are included in a rather untidy hand, and the square notation on four staves has been rendered as little hollow circles. As working notes, it would seem to indicate that musicians are functioning in a fully literate mode. |  |

|

| Musical annotations on blank parchment in a 15th century French book of hours, from a private collection. | ||

| Modern recordings of medieval church music generally represent an reinvented tradition of Gregorian chant. The music has been reassembled from various sources and reinterpreted, usually in the form of unaccompanied monophonic chant. This may be what has survived from the written record, but what do we make of the multitudes of depictions of musicians, not only in secular manuscript contexts, but in church art? They appear in the most sacred places, playing an amazing variety of instruments. | ||

|

|

|

| An angel plays a harp in the choir of Lincoln Cathedral above, while a multi-instrumentalist adorns Chartres Cathedral at right. | ||

|

One figure playing pipe and tabor and another playing a stringed instrument are among multitudes of musicians adorning the blind arcading in the nave of Beverley Minster in Yorkshire. | |

|

An angel plays a trumpet in a battered stained glass window in the parish church of Thornhill in Yorkshire. | |

| Perhaps our reliance on the written word has blinded us to some of the musical traditions of the church, passed on through oral tradition and preserved only in representations in stone and glass. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||