Many

medieval fonts depict the seven sacraments.

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Religious Instruction and Commentary | |||||||

| Christianity is known as a religion of the book, based in one single authoritative text, the Bible. However, the Bible is in no sense a complete guide to Christian worship or ritual or to how the church should be organised. Much of it consists of a long series of concisely written narrative episodes, sprinkled in the New Testament with moralising sermons, parables and epistles. The songs of praise to God known as the Psalms and the mad hallucinogenic imagery of Revelations stand in strong contrast to this sparse commentary, while the erotic love poetry of the Song Of Solomon has ever been a bit of an embarrassment to a religion preaching chastity and temperance. |

|

||||||

| Samson carries the gates of Gaza in an episode of Biblical narrative, as depicted on a misericord in Ripon Minster. | |||||||

| Nevertheless, Christianity has always been a religion of the written word. The progressively prescriptive demands of an authoritarian church were enforced through the use of written texts. While the Bible itself was an inadequate text for delineating the conduct of the Christian religion, the church developed a whole series of authoritative texts for this purpose. At all stages, the writings of those whose opinions or interpretations were not in accordance with those in authority in the church could be declared heretical and banned. While thinking men struggled to comprehend the complexities of their religion, church bureaucrats used their writings to enforce conformity. | |||||||

| From the earliest Christian times the writings of the fathers of the church from the desert lands of its heartland formed a core of instructive works. The homilies of these early fathers were part of the armoury of the missionaries who carried Christianity across Europe and formed the basis for the patristic literature. Many of those authors have become little known to us today. | |||||||

|

|||||||

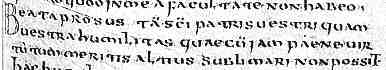

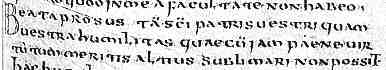

| A segment from the Homilies of St Caesarius, from a copy of around 700 AD (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 9850-52, f.134). The script is uncial. (From New Palaeographical Society 1904) | |||||||

| Text versions in English translation of a steadily increasing sample of patristic works, and of the other works of instruction and commentary discussed on this page, can be found on the web on Early Christian Writings or Guide to Early Church Documents or The Ecole Initiative or the Early Church Fathers section of the Christian Classics Ethereal Library. | |||||||

| The patristic literature was extended by the works of the pioneers of Christianity in western Europe. Their commentaries, philosophies and exhortations built up into a complex of works which drew on earlier writers and developed a complexity of links. In the absence of intellectual property laws, concepts, themes and even specific texts were constantly reintegrated and reinvented with new variations. The church permitted intellectual debate provided it had the last word if the boundaries of acceptability were breached. Spirituality and philosophy were thus woven into the previously spare writings of the church. |

|

||||||

| Columbia University displays leaves from 9th century copies of the Etymologiarum of Isidore of Seville (Plimpton MS 127, frag. f.4) and the Homilies on Ezekial of Gregory the Great (Plimpton MS 53, f.1v). | St Martin of Tours, St Jerome and Pope Gregory the Great guard the portal of the north porch of Chartres Cathedral, as their works and deeds guarded the developing church. | ||||||

| There were works on how the religious life should be conducted. The Rule of St Benedict, written in Italy in the 6th century, was copied and recopied as it became the basis for the many variants of western monasticism. The rule is brief and concise, and strange to say, it still makes a fascinating read today. It should be prescribed for study in all modern management training courses. (See McCann 1976) The 5th century Rule of St Augustine was revived in the 12th century and adapted for use by the monastic communities involved in service rather than the pure worship of God in enclosed communities. | |||||||

|

The mode of living set out in the Rule of St Benedict established the plan for all Benedictine monasteries and their derivatives, as shown here at Gloucester Cathedral, formerly as major Benedictine abbey. The church on the right is attached to the quadrangular cloister from which the photograph has been taken. The arrangements for sleeping, eating and meeting together are prescribed by the rule and its provisions for celebrating the divine office. | ||||||

| Gloucester Cathedral, with the crossing of the church as seen from the cloister with its monastic conventual buildings. | |||||||

| The various reforms of Benedictine monasticism over the centuries were accompanied by their own literature of reform. This became part of the ever increasing body of instructive material. | |||||||

|

At left, a statue of St Bernard of Clairvaux in the church of the village of his birth, Fontaine-les-Dijon. At right, the austere architecture of the church of Fountains Abbey, a Cistercian house in Yorkshire |

|

|||||

| The reforms of the Cistercians, as expounded in the writings of St Bernard of Clairvaux, imposed simplicity and conformity, as reflected in the severe architecture of the ruined church of Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. It was also reflected in the manuscripts copied in their houses. The medieval statue of the saint in the church in the village where he was born, Fontaine-les-Dijon, shows a more benign figure than the author of the rantings against the excesses of the Cluniacs. | |||||||

| From around the 11th century a series of writers and philosophers provided much of the conceptual framework of the later medieval church. Many aspects of the religion which we may think are based in the very foundations of the faith were formulated, or at least codified, during this phase of consolidation of church authority. Who, apart from a genuine medieval church historian, would have thought that the concept of the seven sacraments was formalised by Peter Lombard in the 12th century? Threats to church authority such as the Cathar heresy fed into a rigidifying of concepts through the authority of the written word. |  |

||||||

Many

medieval fonts depict the seven sacraments. |

|||||||

| You can then add in the prolific scholars of the later middle ages and the productions of the universities, in which even the basic texts were surrounded and buried by minutely and closely written glosses. There is a long tradition of academics being critics and commentators rather than creators. Learned men reintegrated the works of Classical authors into medieval religious thinking. The literature of instruction and commentary on religious matters grew into a massive and groaning pile. Christianity was no longer a religion of The Book, but a religion of an overflowing library. | |||||||

| Significantly, it is all in Latin. On the one hand, this allowed scholars all over western Christendom to communicate, interact and be overseen by the hierarchical authority of the church organisation. On the other hand, ordinary lay people were totally excluded from any process of debate. They did not read this literature. It was absorbed and digested by the clergy, and the concepts fed to them orally through the preaching and lessons of this clergy. It is no coincidence that the rise of preaching orders, notably the Dominicans, coincided with periods of heretical unrest. People had to be told. While the teachings of the church were based on an ever increasing written literature, the lay practitioners of the religion learned their faith in an illiterate mode. Paradoxically, the written word could be used both to spread and confine learning. |

|

||||||

| Blackfriars Hall in Norwich was formerly the vast preaching nave of the Dominican church. It was where the lay people congregated for their religious learning in the absence of a library. | |||||||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||||