If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Personal Devotion and Books of Hours (5) | |||||

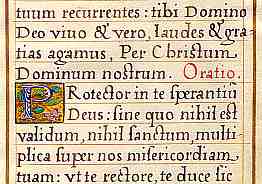

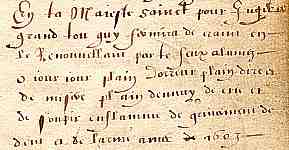

| Manuscript and printed versions of the book of hours co-existed for some time, each influencing the other. While the printed works retained elements of manuscript design, and even handiwork, the scripts used for manuscript works were influenced by the new typefaces, to the point where they look quite awkward and uncomfortable as handwriting. The obsecro te prayer on a previous page is an example of this, as is the very late manuscript example at right, from long after one might think that the manuscript tradition had ended. It has an exquisitely painted little gilded initial with floral motifs. |  |

||||

| Section of a page of a manuscript book of hours produced in 1570, from a private collection. | |||||

| While the printed works must have brought book ownership, and an appreciation of literacy, to a greater proportion of the population, they also served to standardise the text. That is another story. | |||||

| However, if you want to read some of my meanderings on this subject, go to The Concept of Text in the Manuscript Tradition. | |||||

| With either manuscript or printed books of hours, the text was not entirely defined by what the original printer or scribe had included. Individuals personalised their books of hours with various additions, from the simple addition of favourite saints or even family occasions in the calendar, through personally scribed annotations or prayers in the margins or on blank pages, to the addition of formally scribed material. Eamon Duffy, in the book cited at the beginning of this section, has looked at this material in fascinating detail, but the following are just some scruffy little samples from the medieval dustbins of history. | |||||

|

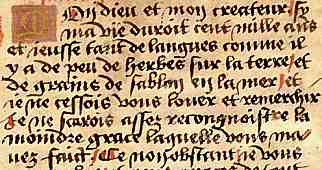

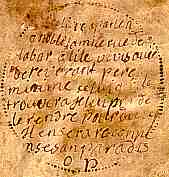

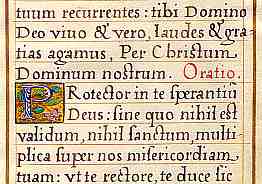

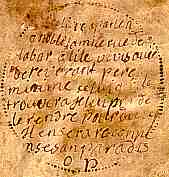

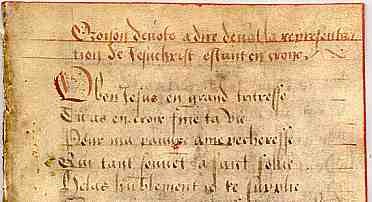

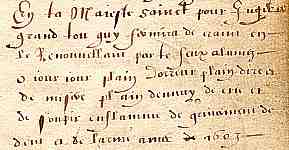

Sample from a page of French prayers from a book of hours of the late 15th or 16th century, from a private collection. Below is the rather scruffily written owner's inscription from the back of one of the pages of the prayer. | ||||

| The example above has been added in what looks like a professional hand, or at least an educated one, and even has a little gold initial. However, the text is not fitted into the usual box in the middle of the page, but is crammed from edge to edge, and has even been slightly chopped off at some stage, presumably when the book was rebound. The text rambles across several pages, sometimes on both sides and sometimes on one side only. One page has an owner's inscription in a roundel on the back. The text has been marked off with little red lines, presumably to aid phrasing, reading and comprehension. The prayers are designed to be used when taking the sacrament at mass. |  |

||||

|

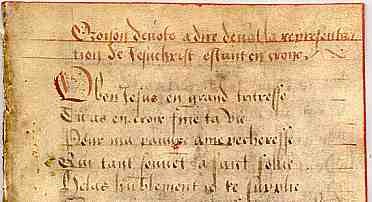

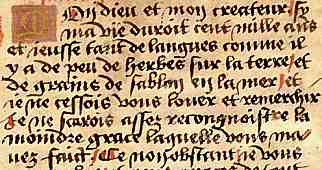

Sample of more added prayers from the same manuscript as the previous example, from a private collection. This addition is dated at the end to 1572. The pages are grubby and faded, but would have once been quite elegant. | ||||

| The same book of hours contained another formally scribed prayer in a completely different hand and page layout. The prayer is to be said before an image of Christ on the cross, and is addressed to the Lord as tu, the very personal form of address demonstrating that these books mediated a very intimate relationship with the deity. The books were thus individualised in their content, and in the religious process that they represented. The prayer shown above is four pages long, and concludes with the date 1572. This may post-date the production of the book by a long time, as they remained in use and were handed down within families, or sold to others, for many years. | |||||

|

Sample from prayers added to the endpapers of a 15th century book of hours, dated 1603, from a private collection. | ||||

| The above example, from a different book of hours, is a sample from two sets of prayers in two fairly informal, personal hands and dated 1603 and 1604. The book of hours was no longer the bestseller that it had been in the 15th century, but clearly there were still people continuing to use and modify books that had been curated for a very long time. The process of continual modification of books with addenda, annotations and glosses was a feature of medieval books of all kinds, and represents a different attitude to text to that which became common in the age of industrial book production. The presence of these addenda in books of hours shows that the process of appropriation and modification of texts was not confined to the intellectual professionals of the universities or monasteries, but was also carried out by more ordinary people in their personal books. | |||||

|

Image of the head of Christ on the veil of Veronica, from a 15th century French book of hours, from a private collection. | ||||

| The capacity of individuals to individualise their books of hours also applied to the miniatures. Patrons could make selections of the saints to be commemorated in the suffrages to saints, for example. In the example at left, an image of Christ's head on the veil of Veronica, derived from a highly apocryphal story of the Passion, has apparently been added to a blank section of page at the end of a section of the text. The image overlaps the line filler above it. The other side of this page, originally blank, contains some prayers in French added in the 16th century. | |||||

| The miniatures in books of hours were more than decoration. They were aids to prayer and contemplation, and served as conduits to the saints commemorated. The images of favourite saints, or those thought to be particularly efficacious in times of illness, stress or childbirth, may sometimes be smudged as a result of having been repeatedly kissed or clutched in sweaty hands. It is tempting to see the smudges on the image above as coming from that source, apparently spoiling the image for art lovers but enhancing its interest to a social historian. | |||||

| The story of books of hours comes to an abrupt conclusion in countries that adopted the Protestant reforms. However, even in Catholic countries their use dropped away. They have a fascinating place in the history of literacy as the text most likely to have been read at the end of the manuscript era. So many of them were floating around that they have been treated rather harshly by antiquarians and collectors, sliced up to remove interesting miniatures and initials and regarded as the Cinderella of the manuscript world. The majority of them may not represent the most sophisticated levels of art, but they do tell us a great deal about human spiritual need. If you should encounter a little orphaned fragment of medieval manuscript out there in the wild world, there is a good chance that it came from a book of hours. People still cling on to the bits, perhaps in the hope of finding some little part of what we have lost. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||