If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Personal Devotion and Books of Hours (3) | |||||

| Other Biblical texts which were often included were Gospel readings for the major church feasts and the seven penitential Psalms. It could also include the Psalter of St Jerome, an abridged version of the Book of Psalms, the reciting of which was supposed to be as efficacious as reciting the complete work. It was supposedly created by St Jerome to rescue those hapless souls who had taken a vow to recite the entire Book of Psalms every day without realising quite how long it was. Assorted prayers to Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and the saints made up the more varied sections of the book of hours. It generally finished with the Office for the Dead, a version of the hours aimed specifically to aid the souls of the departed. The order in which the components were included was not rigid. | |||||

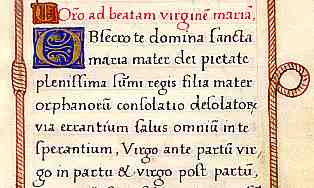

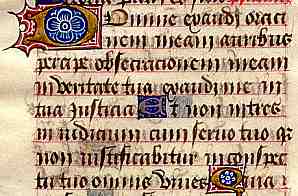

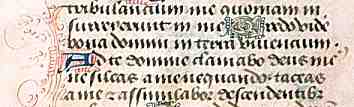

| Two very popular Latin prayers to the Virgin are known as Obsecro te and O intemerata, from their first words. The example at right shows the beginning of the former from an early 16th century French book of hours, very late for the manuscript tradition. |  |

||||

| Sample from an early 16th century book of hours, probably from Paris, from a private collection. | |||||

| These texts represent direct addresses by the laity to the Virgin. This also applies to certain other prayers, including the family known as the Joys of the Virgin, in which each prayer is associated with an episode in the life of the Virgin. | |||||

|

Prayers to Christ, framed in the context of the various stages of the Passion, also involve the pious layman in direct address to higher powers in authoritatively approved language. The use of visual imagery not only adorned the work, but acted as prompts for the content, as in the example at left which contains a series of images of the events and objects of the Passion. | ||||

| Page from a 15th century book of hours (National Library of Australia, MS Clifford 1097/9, f. 65v). By permission of the National Library of Australia. | |||||

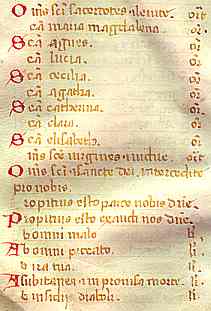

| Prayers to individual saints, referred to as suffrages, were often preceded by a miniature depicting the saint with imagery of their miracles or martyrdom. This part of the book could be varied in content, the selection of saints varying by region or diocese, but also at the request of individual users or buyers. There were some favourites, such as St Catherine of Alexandria, St Margaret, or the entirely mythical St Christopher. |  |

||||

| St Christopher was one of the more popular saints, shown here in a miniature from a 15th century book of hours from northern France (Vatican Library, Cod. Vat. Lat. 14935). From a facsimile. | |||||

|

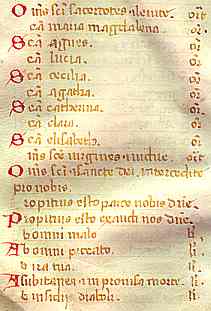

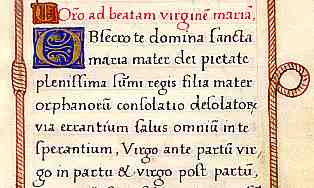

The text could also include the litany, a sort of "come all ye" address to each of the saints in the calendar. Note the use of extreme abbreviation here of repeated phrases, or for ora pro nobis, ort for orate pro nobis and li for liberate. The example at left is a very battered little specimen that was evidently never finished, as only half the coloured intials have been inserted. | ||||

| Part of the litany from a late 15th century book of hours from Italy, from a private collection. | |||||

| Many books of hours were highly formal productions, employing precisely written Gothic textura scripts and much decoration and illumination in the form of initials, borders, line fillers and miniatures. By the later 15th century, however, the histories of scripts were becoming somewhat entangled. Gothic rotunda script, as used in Italy and Spain and as shown on the Italian calendar on the previous page, appeared in books of hours produced in Flanders. The French bâtarde script, derived from the hybridisation of document hands with formal book hands, was produced in sufficiently formal styles for quite elegant productions. | |||||

|

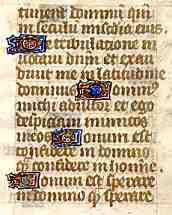

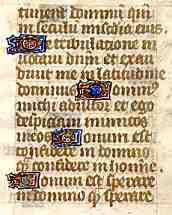

This example of a page with very tiny but quite formal Gothic textura text, complete with gold illuminated initials, is a bit of an enigma. The written area of the page is around 4 x 3 cm, about the size of a large postage stamp and probably much smaller than you are seeing it on your screen. This makes it hard to imagine how it could have come from a complete book of hours. | ||||

| Text of a leaf from a book of hours of around 1420 from Flanders, from a private collection. | |||||

|

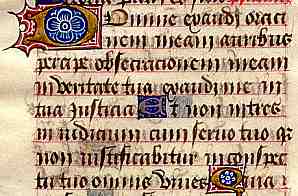

Segment from a leaf from a French book of hours, by permission of the University of Tasmania Library. | ||||

| The above example shows a much less formal and rapidly written Gothic script, with some very extravagant penwork initials, showing some characteristics of bâtarde, such as the long tapering, sloping s. | |||||

|

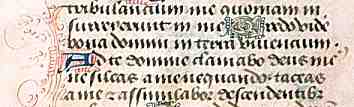

This example shows the bâtarde style tortured into a very formal and fiddly book hand from what must have been a fancy production, spangled as it is with complex illuminated initials. | ||||

| Segment from a page of a later 15th century book of hours from France, from a private collection. | |||||

| The text of the book of hours was originally in Latin, as it would have been pronounced by the clergy in church. While the Latin texts would have had some familiarity to the lay people who had heard them in church, it is not clear how many of them had sufficient Latin literacy to fully appreciate them, or how much they were simply reciting formulae learned by rote. By the 15th century, book ownership had greatly increased amng the laity, and there were also movements afoot to allow them to participate more fully in their own devotions without constant intervention by the clergy. Increasing interest in the cult of the Virgin Mary, saints' cults and the use of the book of hours were all manifestations of these trends. The desire to carry out devotions in the vernacular was a logical extension. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||