If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Personal Devotion and Books of Hours | ||||

|

For much of the earlier middle ages the laity had no books of personal devotion, not even a Bible. They participated in a completely oral culture of religion, listening to sermons and stories, listening to the conduct of divine office or the mass, talking to the priest at confession or less formal occasions, and taking in the rich visual teaching which surrounded them in the church. As the middle ages progressed, the thunderings of the Dominicans and the entreaties of the Franciscans were added for their edification and improvement and, dare one say it, entertainment. Public performances such as the mystery plays were, perhaps, populist in the way that they employed ordinary lay folk as performers and were presented in a public space, but the texts were written by the literate clergy. While one could, no doubt, pray in the privacy of one's own room or chapel, there was no formal process of conducting devotions without the assistance of clergy. | |||

| A Franciscan. | ||||

| The small portable Bibles and psalters that were produced during the 13th century were sometimes owned by wealthy members of the laity, but that does not necessarily mean that they were for individual personal use. Chaplains performed the mass for such people in the private chapels of their castles or manor houses. However, by the 14th and 15th centuries more people were becoming literate and those outside the clergy had a desire to participate directly in spiritual experiences hitherto confined to the clergy or those living under the rule of a monastic order. Mind you, they didn't want to go the whole way with celibacy and continual worship day and night. It had to be fitted into a normal round of life. |  |

|||

| Remains of the private chapel in the ruins of Richmond Castle, Yorkshire. | ||||

| There were books of prayers and books to help you contemplate your sins and various kinds of books of moral improvement. Devotional poems might appear in compilations, possibly copied by the owner of the work. | ||||

|

||||

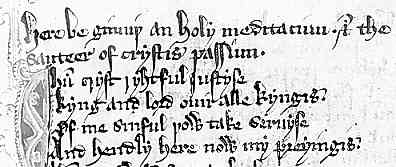

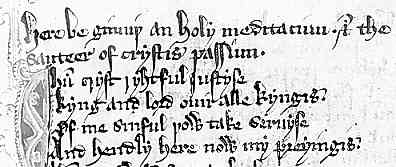

| Segment from a poem Holy Meditation from a late 14th century English volume of religious works in poetry and prose (British Library Egerton 3245, f.193). By permission of the British Library. | ||||

| The use of the vernacular and the simple language of the example above indicates it as a work for the laity, to aid their own religious contemplation. | ||||

|

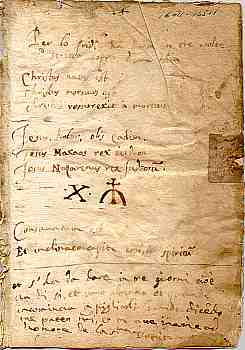

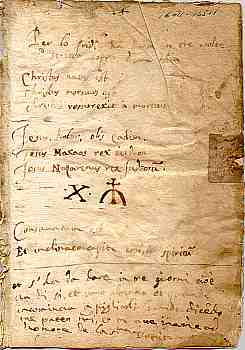

Literate book owners could add their own personal prayers and devotions to other religious works that they owned, which usually had blank sections of leaves or whole blank pages which could be utilised for the purpose. The page at left was formerly the flyleaf of an early 16th century printed Bible, to which have been added a prayer in Latin, religious symbols, and instructions for carrying out the devotions in Italian. It is written in an untidy cursive hand, and has surely been added by the owner of the book. | |||

| Flyleaf from an early 16th century Bible, printed on paper, from a private collection. | ||||

|

|

|||

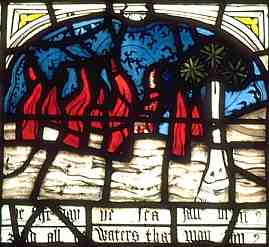

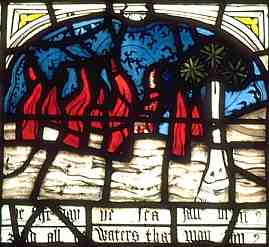

| The Prick of Conscience 15th century stained glass window in the church of All Saints North Street, York; at left the whole window, at right a detail of one panel. | ||||

| The stained glass window shown above illustrates a poem, The Prick of Conscience, which describes the last days of the world. This poem also exists in manuscript copies, but here it is located in a public space. While stained glass windows are traditionally described as texts for the illiterate, this one has the written text of the poem, in English, under each panel of the window. The detail at the right shows and describes the seas burning. The presence of the words must indicate an acknowledgement of increasing vernacular literacy among the laity, as both words and imagery assisted the churchgoer in their religious contemplation. | ||||

| One particular type of work, designed expressly for the laity, became immensely popular, especially during the 15th century. This was the book of hours. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||