If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Works on Gentlemanly Pursuits (2) | |||

|

The garden was an important visual and literary metaphor in medieval manuscript works, employed in texts and in the miniatures that illustrated them. Certain compendia of knowledge had titles that related to gardens or flowers, the flowers being the gems of knowledge that grew within the orderly environment of the garden. A compilation of small segments from the works of others was known as a florilegium. Garden imagery could be used in an allegorical sense, as in the famous poem Le Roman de la Rose. Real medieval gardens were enclosed spaces belonging to aristocratic owners for their pleasure and spiritual uplift. While his lordship was most unlikely to be scratching around in the compost heap himself, the planning and supervision of an orderly and pleasing garden was an attribute of a fine manager of properties and estates. | ||

| Three goddesses in a garden represent life's choices for the author in this 15th century miniature. | |||

| Manuals on horticulture, animal husbandry and estate management were not simple textbooks for rustic yokels, but were part of the education for nobility. In return for the services of his tenants, the feudal lord was obliged to run his estates wisely and well. | |||

| The garden in this manual of estate management is as formal, orderly and filled with beautious aristocratic women (although in some cases more fully dressed) than the allegorical one above. The setting in an architectural enclosure surrounded by tidy estates is similar. But here the lord is having a discussion with the gardener, not making moral decisions. Note that he is bigger than the gardener. This is a social, not necessarily a physical, reality. |  |

||

| From Le Livre de Rusticon des prouffiz rurualx, a French manuscript from the late 15th century (British Library, add. ms. 19,720, f.214). | |||

| Latin treatises on the characteristics and medicinal properties of plants had been copied down through the centuries through the monastic scriptoria. These seem to have remained in the libraries of the literate clergy as samples of the literary knowledge of the world, rather than being adapted into the vernacular as practical knowledge. Like the hunting manuals, the very fine surviving examples of the books of horticulture, husbandry and estate management were designed for the library, not the potting shed. The conceit of placing his lordship in every illustration indicates that this is a work for him, not a manual for the gardener. | |||

|

The rumbustuous and colourful sport of jousting became the ultimate aristocratic recreation. Although it is hard to reconcile with the actuality of large, sweaty, ugly blokes biffing, and occasionally accidentally killing, each other, it was supposed to embody the finer aristocratic virtues of the code of conduct known as chivalry, and of courtly love. This explains the swooning ladies at the top of the picture at left. It was also the occasion for display of the art of heraldry. Men of might could have fine manuscripts made to commemorate especially significant tournaments that they had sponsored or starred in. Treatises on the art of heraldry were studied by magnates great and gentry small. You never knew, John of Gaunt might invite you to dinner and you would want to be able to hold your own in the lads' dinnertime conversation. | ||

| Depiction of a joust in the Manesse Handschrift, a 14th century German manuscript of lyric poetry. | |||

|

|||

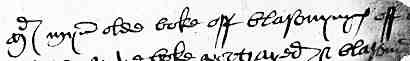

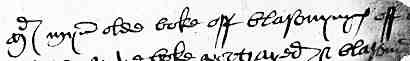

| Segment from a late 15th century damaged list of books among the Paston letters (British Library, add. ms. 43491, f.26), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| The little segment above indicates that John Paston II, a member of the East Anglian gentry, owned a boke off blasonyngys. In fact, he seems to have owned four books pertaining to heraldry, and one about the art of knighthood and tournaments. | |||

| Image of two men playing draughts, from initials or borders of a 13th century psalter from the Library of the Duke of Rutland, Belvoir Castle. (From The New Palaeographical Society, 1905). |  |

||

| People in all stations of life have played board, dice and card games from time immemorial, as attested by archaeological finds of the boards and counters. | |||

| Such games occupied a morally anomalous position, sometimes denounced by the church as representing luxury and vice, especially when betting was involved. In fact, it seems that in the example above, taken from a psalter, one of the participants has literally lost his shirt, not to mention his shoes. Perhaps, in a form of medieval precursor to the old Salvation Army adage "Why should the devil have all the best tunes?", high class books were produced which not only set out the rules and strategies for such games, but also used the games and the attributes of their pieces as a basis for moral homilies. Games like chess could also be seen as embodying feudal values, with the lords, knights and bishops charged with protecting the king while the pawns sacrificed themselves selflessly for their superiors. And given the military obligations of the knightly classes, anything which trained strategic thinking might just come in handy sometime. Almost anything could be given a moral dimension in medieval literature. | |||

| The University of Chicago Library provides a complete digital facsimile of a 13th century moralised chess manual written by a Dominican friar Le Jeu des échecs moralisé. The site Alfonso X Book of Games shows illustrations from a manual of various games, including chess, backgammon, checkers and 9 men's morris from the mid 13th century. Alphonso X was king of Leon and Castile and his book now resides in the monastery library if St Lorenze del Escorial. A complete translation of the work by Sonja Musser Gollady is available as a download in Acrobat format. The Bibliothèque nationale de France has an exhibition Jeux de princes Jeux de vilains showing the depiction of games in manuscripts. | |||

|

|||

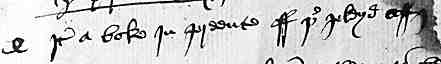

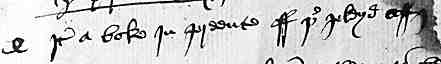

| Segment from a late 15th century damaged list of books among the Paston letters (British Library, add. ms. 43491, f.26), by permission of the British Library. | |||

| Another sample from the list of books of John Paston II, as illustrated above, refers to a boke in preente off the pleye off ....... . The end is chopped off by damage to the document. This is taken by the editor of the modern edition of the collection (N. Davis ed. 1971) to be Caxton's first edition of The Game and Playe of the Chesse published in 1475. In other words a chess manual was deemed by Caxton to be worthy and saleable enough to be among the earliest printed works in English, and a copy was apparently snapped up to appear in the library of a member of the rural gentry. | |||

| Works to teach the upper classes their obligations and manners were not always disguised in this way. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||