|

| Works on Food and Cookery |

| The art of food preparation, complex as it became in the more wealthy households of the later middle ages, was not an art with a legacy of literate teaching. The hierarchy of household service meant that cooks, food preparers and food servers learned their skills through oral teaching, watching, copying and getting an occasional cuff around the ears. There were no gravy stained recipe books propped above the fireplace or on the kitchen bench. Books were too valuable for that. Nonetheless, a literate tradition developed, specifically around the art of the grand meal in the great hall. |

|

A view around the huge kitchen of the late medieval manor house of Gainsborough Old Hall in Lincolnshire, with ovens set into the brick wall at the back. |

| There are two opposing attitudes to medieval eating in the modern conception. One is the rough and tumble, chomping on whole chickens, slurping the gravy and chucking things to the dogs model. The other is a hyper-refined conception of lords and ladies, exquisitely attired, daintily observing the most refined of manners while nibbling on all manner of exotic delicacies and enjoying fascinating diversions. Both are probably excessive extrapolations from what is known about medieval upper class eating. Much of the direct literature on cooking and food preparation comes from the later middle ages, when food, eating and table manners became part of the significata of a desperate era of social competition and conspicuous extravagance. |

|

| At one level, the natures of different foods were analysed and assessed in relation to their healthful properties, utilising principles which derived from Classical writers on medicine. Hot and cold, wet and dry, were characteristics which applied to every dish and method of cooking, and these had to be balanced not only among themselves, but to the health and temperament of the individual diners. Some late medieval texts combined tracts on health with recipes to illustrate the principles. Magnates employed physicians to advise in detail on what they should eat at table, and tasters to check it out first. This is all totally upper class in preoccupation, and although certain principles of food preparation percolated gradually down the social scale, you didn't have to go too far before the major concern was sufficiency. |

|

The interior of the great hall of the manor house of Tretower, in Wales, set up with a bit of hokey medieval paraphernalia and a can of spray-on cobwebs for a television shoot. |

| From the late 13th century, and proliferating in the 14th and 15th centuries, were collections of recipes. Some of the most quoted of these, such as the Forme of Cury, the Viandier of Taillevent or the Buch von Guter Spise derived from the highest social levels in England, France and Germany respectively. As recipe collections proliferated in the libraries of the wealthy and those who would migrate to the higher levels of society, they served a function similar to fancy illuminated psalters, books of hours and elaborate volumes of romance. They indicated that the owners were persons of standing, who knew how to do things properly. They resided in the library, not the kitchen. They concentrated a great deal on the social ritual of the lengthy and elaborate feasts in the great hall, in which a mighty array of courses was served to vast numbers of people. |

|

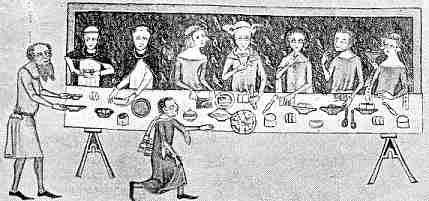

| A depiction of dining from the 14th century Luttrell Psalter. |

| Meals served in the great hall consisted of numerous courses, each of which was something of a buffet, with many different dishes being placed on the table. Diners each had their own trencher, or large slab of bread which served as a plate, and their own personal knife, but no fork, just fingers. It was not a great free for all. Guests were seated according to status and were expected to partake of dishes that were offered to them, observing certain social niceties. An army of retainers carried in food, cut it up for their lords and presumably got fed in the kitchen. Over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, certain courses became elaborated into bizarre and complex forms, serving as entertainment as much as food, until they became inedible and evolved into theatrical performance. As more people aspired to join these social classes, and competition between the members of the upper echelons escalated, it is these complex and elaborate dishes and a monumental scale of production that became emphasised in the books about cooking. |

|

The hall of the manor house at Stokesay, in Shropshire. |

| Grand dining in the great hall required certain social manners, and books of etiquette, sometimes called courtesy books, were produced expounding on all the proper politenesses. The existence of such works might favour the refined model of upper class eating rather than the bunfight model, were it not for a few details found in the texts. |

Readers were advised, among many other things, not to blow their noses on the napkins used for wiping their hands and cutlery, not to scratch at vile parts of their bodies while eating, and not to attempt to spit across the table. If this was refined eating, just how unrefined were the readers that they needed such instructions written down? And who were the readers anyway? In the very hierarchical society of the 14th and 15th century, boys who were sons of the aspiring gentry or lesser aristocracy might act as servants at table to the greater lords. With the established hierarchy being shaken by social competition, young servant boys and people from classes who were not accustomed to this social ritual may have needed a little coaching. Possibly the books were teaching notes for the stewards who were in charge of these junior servants, or were acquired by the aspiring merchant classes just in case they ever got asked to dine with John of Gaunt. They did throw their bones on the floor though, to be swept up with the rushes and herbs that were placed there to improve the general ambience.

|

|

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|