|

|

Religious

Experience |

|

Medieval

Christianity was a religion of authority, and that authority was based

and confirmed in written texts. The literature of the medieval church

tends to be cumulative. The Bible

and the patristic

literature formed a basis for commentary, development of concepts and

debate. Many facets of church belief and practice which we may believe

were founded in the very roots of the religion were developed in the medieval

era, but they were constructed by a continual process of building on and

refining of earlier work. There was, however, some space for works based

on mystical experience and personal divine revelation. This could be a

risky area. The church was always alert to the danger of heresy. |

|

Within

the New Testament

of the Bible the book of The Revelation of St John stands

out as a piece of experiential writing, full of wild imagery, at the end

of a long series of narratives and moral counselling. The images were

reproduced in volumes of the Apocalypse,

but were also turned to moral instructional purpose in representations

of the Last Judgment in sculpture and wall painting. These latter emphasised

the fate of the souls of the good and wicked rather than the strange creatures

and mighty battles that populate the text. The Book of Revelation

was tamed and rendered didactic for public consumption. |

|

Image

from a 13th century French Apocalypse (Cambridge, Trinity College Library,

MS R 16.2, f.14). |

|

|

The

Last Judgment on a tympanum at Rheims Cathedral, showing the fates of

souls. |

|

The

term mysticism is used for processes of unification with God and direct

revelation of God's power and love. Much debate in the medieval church

revolved around the nature and possibility of such revelation, and its

relationship with intellect and reason. This is really intellectual debate

about the philosophy of mysticism, rather than actual experiential writing.

A very early treatise by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, probably a Syrian

monk of the late 5th or 6th centuries, fuelled this debate for centuries

and various translations from Greek into Latin were made of his work during

the course of the middle ages. As an aside, the reason he has a name that

sounds as if it comes from a Monty Python sketch is that for centuries

he was believed to be an individual converted to Christianity by St Paul,

and he even included some fraudulent references to witnessing events of

that time to confound the issue. Funny thing for a mystical philosopher

to do. |

|

| |

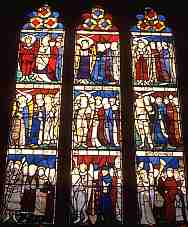

Pseudo-Dionysius

codified the concept of the nine orders of angels, much used in medieval

art, as in this stained glass window in All Saints, North Street, York. |

|

There

were those who claimed experience of divine revelation, but they did not

all write treatises on the subject. St Francis of Assisi received the

stigmata, or wounds, of Christ. Modern psychologists would no doubt have

a bit to say about that, and the medieval church found Francis a bit of

a problem at times. Once he had safely expired they could make him a saint

and build a nice big church with lovely frescos in his honour. He did

not leave any autobiographical text of his personal religious experience. |

|

The

church of St Francis in Assisi. |

|

Recording

personal religious experiences required ratification by the church. In

the early 12th century a young and sickly Hildegard of Bingen started

receiving prophetic visions with startling imagery. At around the age

of 40, when she had achieved the status of superior of a Benedictine convent,

she became convinced that these were divine revelations which should be

recorded and publicised. Hildegard could not write. The abbot who supervised

her community ordered a monk to write down her descriptions, but the work

had to be examined by the bishop and clergy of Mainz, the bishop of Verdun

and Pope Eugene II before it could be accepted as the divinely revealed

word of God. Her major work, called Scivias,

was printed in Paris in 1513, by then an acceptable work of religious

writing. Hildegard is still known today, but mainly for her church music

which continues to be recorded. Medical experts who have examined descriptions

of her revelations in detail are convinced that she suffered from serious

migraines, but God reveals himself in mysterious ways.

|

|

continued |

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|