If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| English Chancery Records (3) | |||

| In the 13th century, the king began to send instructions to the Chancellor for the issuing of material under the great seal in writing, rather than issuing verbal instructions. The privy seal was used to authorise these documents, or warrants. The privy seal is sometimes referred to as the small seal or secret seal, indicating a rather more personal instrument than the bureaucratic office of the Great Seal. However, in the 14th century the office of the Privy Seal was set up in its own headquarters in Westminster, rather than travelling around with the court. The office of the signet became the closest to the king, and the place where processes were often set in place. Those processes became quite complicated. | |||

|

The privy seal attached to a document of Richard II, from 1378. | ||

| The privy seal and the signet were single sided seals attached to the face of the document, unlike the great seal, which was double sided and appended to the document with a strip of parchment cut from the lower border of the document, or attached with separate parchment strips. | |||

|

A rather desperate reproduction of the signet, in this case the Signet of the Eagle, used by Henry VI on a document of 1441. You might be able to just make out a somewhat emaciated eagle in the central splodge. | ||

| In its most elaborate form, bureaucratic action involved a series of written processes. A request to initiate action might be sent to the king as a petition. | |||

|

|||

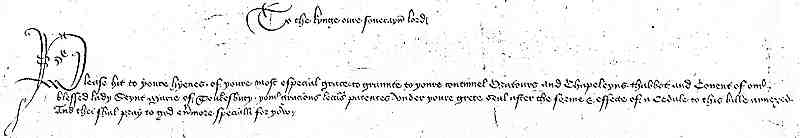

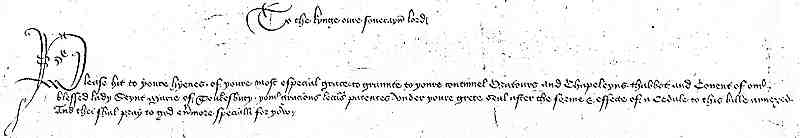

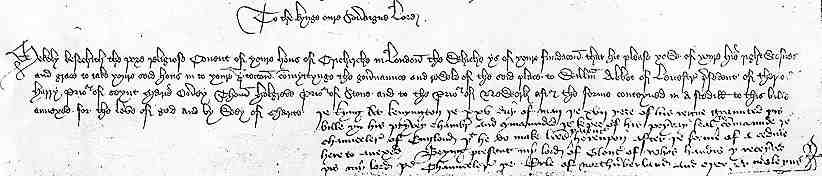

| Petition of 1449 of the abbot and convent of Tewkesbury (National Archives, E.28/79/30). By permission of the Natonal Archives. | |||

| The petition, or bill, was addressed to the king. It could be a concise and formal document which simply drew some matter to the king's attention. The details of the matter were sometimes included in a separate document included with the petition itself. The above example refers to a cedule to this bille annexed. | |||

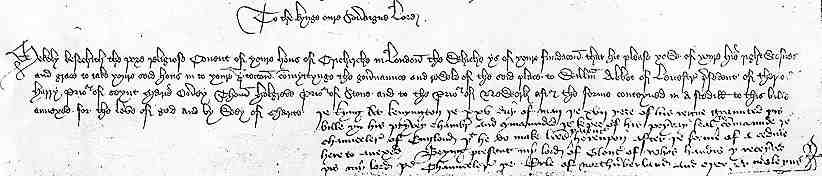

| Dealing with this matter could, at its most elaborate, entail the king's secretary writing a warrant under the signet which was sent to the Keeper of the Privy Seal, who then forwarded a warrant under the privy seal to the Chancellor, who in turn arranged letters patent or letters close under the great seal. Sometimes the original petition was endorsed with a note on the actions to be taken by the Privy Seal. | |||

|

|||

| Petition of 1439, with endorsement on the lower right, from Christchurch Convent, London (National Archives, E.28/60/38). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

|

|||

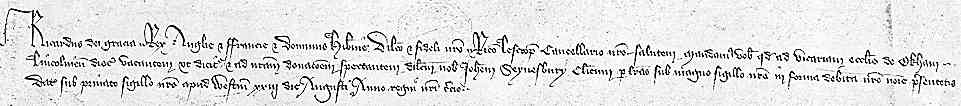

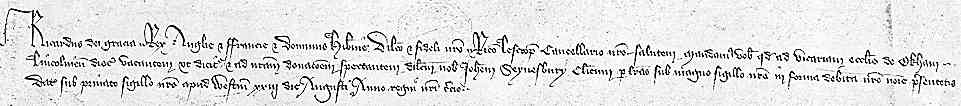

| Warrant of Richard II (National Archives, C.81/461) under the privy seal ordering letters under the great seal appointing John Seynesbury to the vicarage of the church of Okeham. By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| Neither the office of the Privy Seal nor of the Signet made copies of their outgoing correspondence on rolls. The documents themselves were kept by the recipients and filed. Warrants were therefore preserved as many individual small documents. Many writs sent out from the Chancery were also not enrolled, if the recipients did not pay to have this archiving service performed. Some writs, particularly those directed at officials such as sheriffs, had to be returned to a royal justice to ensure that they had been received and acted upon, and these were returned to the Chancery and filed. Any single item of business could therefore generate a whole series of documents: petitions, annexed schedules, endorsements, warrants, writs, letters patent, letters close. These encapsulated the stories of dealings between the monarch and his subjects. But then something nasty happened to the filing system. | |||

|

An amazing array of English governmental records has been preserved from medieval times, but until the 19th century there was no single repository. The Public Record Office was founded in 1838, on a site with significant historical continuity in Chancery Lane, where a home for converted Jews had been handed over to the Master of the Rolls in Chancery after the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290. The modern Public Record Office housed not only the old Chancery records, but also Exchequer and legal records, and later records from Wales and the Palatinates of Lancaster and Durham. | ||

| The Chancery Court in the late 15th century, as depicted in a manuscript illustration in the Inner Temple Library. The Chancellor and Master of the Rolls are seated at the top while everyone else gets on with the work. By this time the Chancery was also exercising some judicial functions. | |||

| The transfer of massive quantities of material to form the new archive resulted in a great deal of confusion, and the provenance of much material was lost in the transfer. Materials were archived, not as sets of documents relating to particular pieces of business, but according to categories devised by archivists. Petitions, warrants and letters were separated. Some material was deposited in unsorted and uncatalogued sacks of miscellanea, and highly reliable sources inform me that they are still there. A huge ongoing process of publication of calendars, which are really abstracts, of archived material gives researchers a start, but there will be work for medievalists to do for centuries if they so choose. The Public Record Office is no longer in its place of ancient continuity in Chancery Lane, but in new premises in Kew, and is actively engaged in the process of bringing historical understanding of the records to the public. It has recently merged with the Historical Manuscripts Commission to become the National Archives. | |||

| It was not until well into the 20th century that local record offices were established in Britain. These have served as magnets to attract many dispersed documents such as charters, deeds or letters which had, through their original intention or through accidents of history, found their way into private hands. Medieval material continues to be deposited in these archives and fills some of the gaps in the central records. The trick is in finding and correlating the many dispersed documents. | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||