|

|

Drama

(5) |

|

By

definition, purely oral peformance leaves no written traces, but there is

evidence from written and pictorial sources that it was there. The portrayal

of musicians in many forms of medieval art indicates that musical performance

was culturally significant. |

|

A

hurdygurdy player performs on a 14th century label stop in the nave of Beverley

Minster, while a bagpiper puffs out his cheeks on a 15th century corbel in

St Mary's church, also in Beverley. |

|

|

Performance

spectacles, in both public areas and in the dining halls of the gentry,

included juggling and acrobatics, wrestling, games, and animal performances

such as bear baiting, which would now be considered very incorrect. Minstrelsy

involved music, poetry and performance. Mumming or disguising involved

participants in costume invading an event and presenting a tableau or

mime. Public mumming was prohibited in many places in the 15th century,

presumably because it involved cloaking one's identity in a public place,

which could be used for those getting up to no good. No doubt it still

provided a good party trick. Froissart, in the late 14th century, describes

a particularly unfortunate case in which some members of the flower of

the French aristocracy were burnt to death by arriving at an occasion

in inflammable costumes, and some idiot came up with a torch to try and

find out who they were. |

|

|

|

|

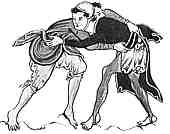

Images

from the initials and borders of a mid 13th century psalter in a private collection

show a tumbler, two wrestlers and a piggyback wrestling match. |

|

Aristocratic

spectacles included the tournament, in which the concepts of chivalry

embodied in the romances

were transformed into live action spectaculars. Although disapproved of

by the church, they were tolerated as means of training the defenders

of Christianity. They were affirmative of class structure. They were also

dangerous. While they were non-literate events, they certainly had elements

of theatre. |

|

Illustration

of a tournament at St Inglevere, near Calais, after an illustration in a manuscript

of Froissart's chronicles in the British Library. |

|

Public

spectacles in the towns could include civic pageants which were staged on

big occasions. Public punishment was also performed in theatrical mode, whether

in the form of shaming rituals in which miscreants were forced to wear strange

clothes, or arranged in humiliating poses, while the town musicians piped

them out of the city gates, or the full public execution, with nasty things

done to bodily parts. |

|

The

fate of a baker selling short weight loaves. |

|

The

theatrical ritual and pageantry of the town and the aristocracy may be preserved

for us to some degree through written description and reference, or even prohibition.

That of the rural areas is much harder to know clearly. Ancient agricultural

rituals of birth, death and renewal have become entangled with Christian values

and rituals. These have been suppressed, forgotten, rediscovered and reinvented

until what passes for traditional rural festivity and display is simply a

jumble of mangled fragments. People bounce around in costumes made from shredded

fabric or tie bells around their knees and hit each other with sticks, but

what it really has to do with medieval village folk display is anybody's guess. |

|

The

performance known as The Mummer's Play, which is a parody of the death

and resurrection theme involving St George, has no written texts earlier

than the 18th century. There may be concepts there from local theatrical

events of the distant past, but continuing revision and innovation has

obscured them. Perhaps the only relationships to medieval mummery are

the general concepts of parody, buffoonery and the disguising of identity. |

|

|

Court

mummers, after a manuscript in the British Library. |

|

Puppet

shows are depicted in medieval manuscripts,

as in the example at left. It looks like a Punch and Judy show (there

is a man with a big stick), but is that merely a debasement of an earlier

form of theatre? And were these shows mainly for the entertainment of

children? Perhaps, like animal fables and fairy tales, these are a form

of entertainment that has moved from the general to the purely childish

arena. These pictures of puppet shows are found as marginalia in important

volumes of romance or psalters,

in that strange juxtaposition of rustic imagery with significant texts

that is such a feature of the 14th century. |

|

Marginal

illustration in a mid 14th century copy of the Romances

of Alexander in French verse, of all things (Bodleian Library,

MS Bodley 264, f.54). |

|

|

The

relationship between oral performance and literate drama is hard to assess,

as each may have drawn, to some degree, on the other. In England the earliest

fragment of the text of a play about Robin Hood dates to around 1475, about

the same time as such a play is referred to in one of the Paston letters.

There are suggestions that these may derive at least partly from village May

Games. However, the late 13th century French play Le

Jeu de Robin et Marion was a courtly pastoral piece which had nothing

to do with lusty Saxon yeomen leaping about the greensward in Lincoln green.

It seems that literate aristocratic culture and illiterate festivity may have

been crossing over in various directions. |

|

When

Shakespeare and his pals set up their theatres in London and brought a new

commercial aspect to staged drama, they were building on vigorous living traditions,

albeit battered by religious change. They used them too. |

previous page

previous page |

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|