If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Drama | |||

| It is a cliche to claim that the formal theatre disappeared along with the Roman Empire, to be replaced in the middle ages with dull and didactic religious drama authorised by the church. Then suddenly in the 16th century, bingo! Shakespeare and Marlowe and Ben Johnson and Beaumont and Fletcher suddenly leapt out of a hole in the ground and the modern theatre was born. It wasn't quite like that. The history of medieval drama is a story of the intricate relations between text and performance, between secular entertainment and religious teaching, between oral and literate culture. | |||

| A good general introduction to medieval drama is G. Wickham 1980 The Medieval Theatre London Wiedenfeld and Nicolson. Records of Early English Drama (REED) represents an international scholarly project to locate, transcribe and edit all documentary evidence relating to drama, minstrelsy and public ceremonial before 1642. An ORB article by Carolyn Coulson-Grigsby Medieval Drama: Myths of Evolution, Pageant Wagons and (lack of) Entertainment Value attempts to debunk some now very outdated theories about medieval drama, but has an extensive bibliography. Medieval Drama Links provides links to some of the better web resources on this subject. Medieval and Renaissance Drama contains plain text editions of the texts of many plays. | |||

|

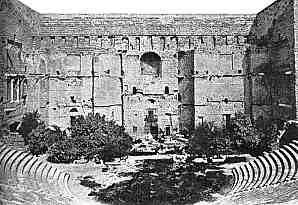

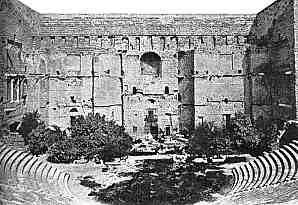

The Roman theatre at Orange in Provence, where many fascinating Roman remains are still upstanding. | ||

| The Roman legacy included large and substantially built theatres, a few of which survive today. Ancient written plays ceased to be performed in them, but do we believe that they served no purpose at all because we have no written record of it? The Dark Ages are only dark to us, because essentially non-literate cultures have left no record of their activities, but it is most unlikely that they had no public spectacle or oral entertainment. | |||

| The church was the literate area of society, particularly in the earlier part of the middle ages, so what we know about theatrical performance is greater in the religious domain. Plays by Classical Roman authors were transcribed in the monasteries, but were not performed. They were part of that body of Classical literature which was curated and studied for its value to the learning of Latin literacy. By this means, the products of those authors are known to us. |

|

||

| Illustration of a character from from a 12th century copy of the Classical comedies of Terence (Bodleian Library, Auct. F.2.13, f.105). (From New Palaeographical Society 1905) | |||

|

The church had its own form of performance in the mass, the divine office, music, processions and Easter rituals. These had elements of theatre, although much was conducted out of sight of the general public behind the screens of the chancel. However, there was costume, a written script, singing, sounds, smells and the richly decorated interior of the church; a setting which itself must have seemed more theatrical than real to many of the occupants of cold, drab homes in town or country. | ||

| A tableau of the mass, with priest and acolyte, set up at an altar in Gloucester Cathedral. | |||

| Around the 10th century, church music became more elaborate, with increasingly intricate variations added to the simple monophonic music known as Gregorian chant. Elaborations known as tropes were added to certain significant passages. Ethelwold, bishop of Winchester and part of the 10th century reform of Benedictine monasticisim in England, wrote some instructions for the earliest recorded form of liturgical drama in his Regularis Concordia. At a significant point in the celebration of Matins at Easter, during the performance of the tropes, four brothers were to enact the three Maries and the angel at the empty sepulchre of Christ. This was a sung performance, and the actors wore ecclesiastical vestments, but it was the beginning of a process of bringing theatrical performance into the nave of the church and to the eyes of the laity. |

|

||

| The 15th century Easter sepulchre at Patrington church, Yorkshire, showing Christ rising from the tomb and the sleeping soldiers. | |||

| Easter continued to be a season of church performance. The late medieval Easter Sepulchres still occasionally found in churches great and small show church art and architecture reflecting theatrical performance, as the imagery carved on these sites of Easter ritual reflected the later staging of religious drama. | |||

|

These liturgical dramas became elaborated through into the 12th century, including a Christmas Nativity and a performance of the story of the Magi at Epiphany. A whole series of productions developed around the Christmas season, including dramas associated with St Nicholas, the slaughter of the innocents, exhortations of the prophets and episodes from the life of the Virgin Mary. These spread to Italy, France, Germany and Ireland. Also associated with the general Christmas season were a series of rather strange inversions which formed a sort of parody of the liturgy within the church. The Boy Bishop, the Feast of the Ass and the Feast of Fools had the parts of senior clergy taken over by deacons or children and some rather odd things went on. It seems that many cultures around the world need to take time out to mock their most august institutions. In this case, it appears to have been part of a developing theatricality in the practice of Christian religion. | ||

| 14th century stained glass window in the nave of York Minster, depicting the adoration of the Magi, as it was performed in religious plays. | |||

| The early liturgical dramas were performed within the church and were conducted in Latin, the language of liturgy but not of the people. In the late 12th and early 13th centuries there was a rise in vernacular literature in the form of romance. Performances of gestes or romance poems were part of the popular entertainment in the halls of the aristocracy. Some poems of Christ's Passion in the vernacular appear at this time. Poetry was not just written text, it was performance. Drama was naturally performance, but it was about to also become vernacular literature. | |||

| A stimulus for the development of vernacular religious drama performed outside the church was the establishment of the Feast of Corpus Christi, announced by Pope Urban IV in 1264 and instituted by Clement V in 1311. This new festival required the exposition of the themes of Fall, Redemption and Judgement. It was also held in midsummer when days were long and the populace at large were in festive mood. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||