If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Domesday Book | |||

|

|||

| Segment of the Bayeux Tapestry, detailing the events of 1066. | |||

| When a Norman called William conquered England in 1066, he brought with him French bishops and barons to oversee and supplant the existing Anglo-Saxon church organization and aristocracy. He also enforced a feudal system in which all lands were the direct property of the king, or held for him by his tenants in chief. He is reported to have expressed the desire to bring the English people under the written rule of law, rather than the process of oral testimony and legal process that they were currently practising. | |||

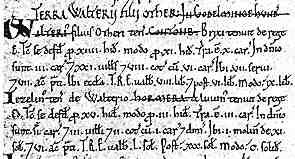

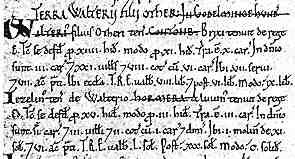

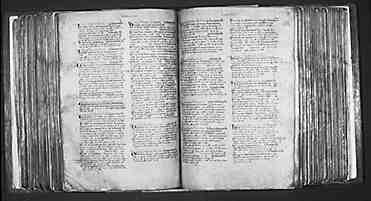

| Segment from Domesday Book (London, National Archives). (From Steffens 1929) |

|

||

| The precise function of the massive survey of the greater part of England, known as Domesday Book, has been the subject of some debate. What it does represent is a significant point in the process of putting legal affairs into writing. The Domesday survey is a listing of all the lands held by the king, his ecclesiastical tenants in chief, barons and even fairly humble landowners. It indicated which lands were held by their tenants in the days of Edward the Confessor, thus referring to Anglo-Saxon tradition as well as new Norman realities. It lists land areas, monetary value, certain resources and numbers of tenants and villeins. It is arranged by county, and within that by the tenants in chief, forming a sort of snapshot of feudal holdings in each county. The information was acquired by groups of comissioners touring the country taking sworn oral testimony from juries in each village or hundred (a pre-Conquest jurisdiction into which the counties were divided). | |||

| A discussion of Domesday book and its function can be found in Galbraith (1949), and there is some material in Bagley (1972) and in Clanchy (1993). Documents Online : Domesday Book from the National Archives in London now allows you to search both volumes of Domesday Book using various criteria, and for a modest fee download full colour reproductions of individual pages along with a modern English translation. There is also background material available on the Domesday Explorer Web Site, which also serves as an ad and help file for an extremely expensive CD-ROM edition. | |||

|

|||

|

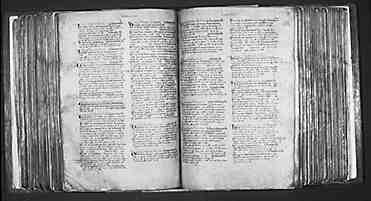

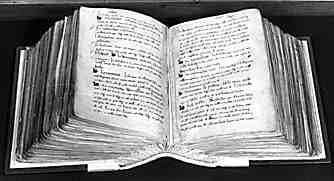

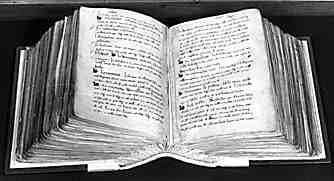

Above, the main volume of Domesday Book; at left Little Domesday Book, as displayed in the National Archives, formerly the Public Record Office, London. | ||

| Domesday Book survives as two volumes, in fact. The first volume surveys all the English shires apart from the northern counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland and Durham, and the East Anglian counties of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk. The East Anglian counties are dealt with in the second volume, known as Little Domesday. The second volume deals with the material in much greater detail, for example enumerating the livestock held by each landholder. Both volumes must have been compiled from a large archive of material collected by the commisioners, but this has all but disappeared. William the Conqueror may have wanted to put legal process into written form, but the art of archiving was not yet developed. | |||

| One original document which may represent a fragment of this archive is the so-called Exon Domesday which survives in the library of Exeter cathedral. It contains the very detailed information, such as is found in Little Domesday, for the counties of Devon, Cornwall, Somerset, Wiltshire and Dorset, but is in a confused and unfinished form. Another fragmentary document, the Inquisitio Comitatus Cantabrigiensis, provides detailed descriptions, village by village, of parts of Cambridgeshire. The Inquisitio Eliensis is a document providing Domesday information for the lands of the abbey of Ely. Both of these survive only in 12th century copies. Documents in the royal treasury, referred to by various writers as having been ordered by William the Conqueror for the description of England, are last mentioned in writings of around 1130. | |||

|

Exeter Cathedral, home of the Exon Domesday. | ||

| The function of the Domesday survey could be seen as the compilation of a data bank for the various taxes, charges and services that the king could make on his feudal tenants. It also became an authoritative reference in cases of dispute regarding landholding or feudal privileges. There is some difference of opinion about how much it was actually used in the couple of centuries immediately after its production, Galbraith (Galbraith 1949) seeing it as an indispensable document lugged around by the Exchequer wherever they went, while Clanchy (Clanchy 1993) claims that there is negligible evidence that it was actually used much at all before the 13th century. | |||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||