If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Diplomas | |||||

| The term diploma refers to the most formal type of document produced by a monarch, magnate or pope. It is essentially a charter. However the diplomas produced on the continent of Europe had certain formal qualities which differed from those of English kings. English royal charters and writs had their own historical path of development. Papal bulls were also diplomas, but as they had some unique features of their own, they will be examined in a separate section. | |||||

| Diplomas evolved from forms of documentation used in the Roman Empire and the earliest medieval examples, from Ravenna and from the Merovingian chancery in France, even copied the feature that they were written on papyrus. While this gave way to the use of parchment, another feature that was retained from Roman times was the use of extravagant calligraphy for very formal documents. Chancery hands in Europe had letters with long, exaggerated ascenders and descenders and a tendency to cramped, narrow forms. While the scripts, and their embellishments, changed over the centuries, the basic style was retained throughout the middle ages. |

|

||||

| The Emperor Justinian as depicted in mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna. | |||||

|

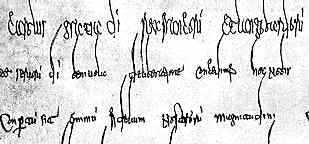

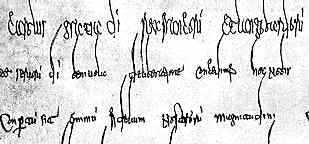

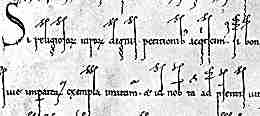

The exaggerated script of a diploma of Charlemagne of AD 781 (Marburg, K. Preussisches Staatsarchiv). (From Steffens 1929) | ||||

|

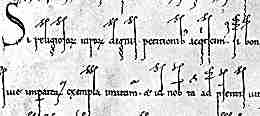

The extravagant calligraphy of a diploma of Emperor Konrad III from 1139 (St Gall, Stiftsarchiv). (From Steffens 1929) | ||||

| The exaggerated and difficult handwriting might suggest that the diploma was more of a symbolic object than a literate record of a transaction. However, while many features were undoubtedly meant to be impressive and to identify the ceremonious nature of the document to anyone who saw it, the construction and validation of the document were in a truly literate mode. Authentication of the document involved a very complex series of written insignia. Diplomas were signed and dated. The solemnity of the document was emphasised by various religious symbols, ceremonial language which could include references to the benefits that the grant may confer on the soul of the grantor, curses upon the heads of anyone who did not observe the instructions in the document, and sometimes an invocation to the deity. | |||||

| As well as written validation, the diploma was authenticated by seal. Until around the 12th century, the seal did not dangle down from the document on tags or strings, but was attached to the face of the single sheet document. Obviously this means that, unlike English royal seals, the seal only had one side. While the process of sealing with wax derives from the very simple and practical method of closing a letter, and ensuring that the recipient knows that the letter has not been opened, these documents were delivered open and the seal was for authentication. |

|

||||

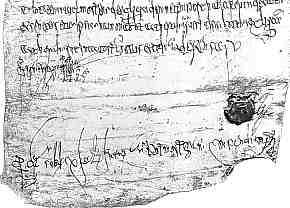

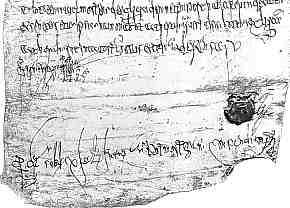

| Bottom of a diploma of the Merovingian king Childebert III from AD 695, showing the seal attached to the face of the document (Paris, Archives nationales, K3, Nr.9). (From Steffens 1929) | |||||

|

Seal of the Emperor Henry III on a diploma of 1053 (Koblenz, Königleich Preussisches Staatsarchiv). (From Steffens 1929) | ||||

| This seal is attached to the face of the document and represents the emperor in majesty, an image which became virtually universal for royal seals, having originated with Otto III. | |||||

| In the later middle ages, seals were attached to the document by cords or tags, often silk cords as had been done for centuries with papal bulls. | |||||

| The Vatican Library Secret Archives shows a diploma of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa from 1164 which not only has the seal attached with silk cords, but has a seal of gold, outdoing even the pope. | |||||

| The function of these documents was the issuing of a major order or instruction, or more commonly, the granting of privilege including the rights to land. The recipient might be an individual, or an institution such as an abbey which depended on such grants to function. Given that the monasteries were the keepers of libraries and custodians of the written word, it seems probable that monastic documents might have a higher rate of survival. Certainly they are well represented. | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||||