|

|

Deeds |

|

In

our literate and bureaucratic society, the ownership of a parcel of land,

a house or a commercial property involves highly specific and specialised

documentation. In the middle ages, the attesting of ownership changed

from oral to written testimony, but the degree of precision found in the

written documentation of today is a modern phenomenon. Even in the later

medieval era, much still relied on verbal understanding. |

|

|

The

ruins of the castle of Ravensworth in North Yorkshire, with the village behind; a relic of the traditional relationship between feudal landholder and village. |

|

In

rural areas and villages, property holding was tied up with the changing intricacies

of the feudal system. Real estate could not be freely traded, nor could its

disposal be specified in wills. Rights to the use of land were granted progressively

down the feudal tree. |

|

Late

medieval houses in the wool manufacturing town of Lavenham, Suffolk. |

|

In

towns, merchants and craftsmen could buy and sell town properties. However,

proof of ownership was not recorded in some central register, but was embodied

in the documents recording rights given by grant or negotiated at law. |

|

The

classes of documents which served as title deeds

to land or property are those that have already been discussed in this

section. Charters,

writs or letters

patent served as proof of ownership by grant, while indentures

or final concords

served to document changes of ownership by legal agreement or lawsuit.

The individual documents which were in the hands of landholders or property

owners served as their title deeds. |

|

From

the beginning of the 13th century, royal grants were recorded on chancery

rolls. Monasteries

and aristocrats kept cartularies

in which copies of such documents were recorded for reference. Courts

kept records of cases involving property transfer. If the instrument of

transfer was a final concord, the agreement was recorded in the feet

of fines. Manorial tenants who were involved in cases pertaining to

landholding could receive a copy of the report in the manorial court

roll, which served as a title deed. In other words, there was no central

repository for records of land ownership. |

|

Stokesay

Castle, a medieval manor house still in a rural setting. |

|

Manorial

lords needed records of the holdings of their tenants, as well as of the

services due to them from those tenants. Various classes of documents

which can be generally categorised under the heading of surveys

were constructed for this purpose. Extents

or terriers listed

the holdings of the tenants of a manor and the rents or services due,

and might include a listing of the stock and crops grown. Rentals

were more concise documents listing tenants, the acreage held by each

and the rent due. Custumals

detailed tenure, as well as the customary law of the manor as followed

in the manorial court. None of these constitute title deeds as such, but

record land tenureship lower down the social scale. |

| The

great grandfather of all land surveys in England was Domesday Book which, with

its various components and addenda, comprised a survey of royal holdings throughout

most of the kingdom. This was a unique document. |

|

|

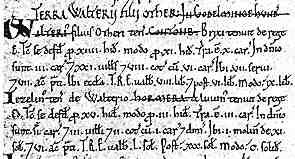

Segment

from Domesday Book (London, National Archives). |

|

The

earliest Anglo-Saxon diplomas

referring to land grants described the parcel of land in great detail,

with topographical details elaborated so carefully that the boundaries

can be plotted on a modern map. The later form of document derived from

the Anglo-Saxon writ of Edward the Confessor relied much more on oral

knowledge. Right through the middle ages, documents referring to land

grants or transactions identify the plot of land in only the most general

terms, relying on the testimony of living witnesses to deal with any disputed

details. |

|

|

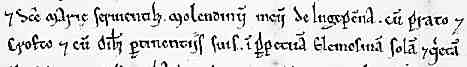

Detail

of a charter of Gervaise Payne to the nuns of Nuneaton, late 12th century

(British Library, add. charter 47424). By permission of the British Library. |

|

The

property in question in this private charter above is described only as

molendinum meum de Ingepenna cum prato et crofto,

my mill at Inkpen with its meadows and crofts. The parties to the agreement

were expected to know which ones. |

|

|

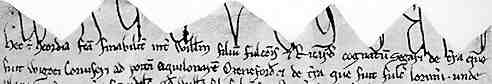

Top

of an indenture of 1190 which deals with ownership of a tenement in Oxford

(Christ Church, Oxford). |

|

Town

properties were described in similarly non-specific ways. The above indenture

refers to a tenement ad portam aquilonarem Oxenfordie,

by the north gate of Oxford. It is not until the 16th century, when the

procedures of surveying and mapmaking became more professional, that reliance

on oral testimony is replaced by more precise written maps and surveys. |

|

Documents

testifying to land ownership or tenure are widely scattered. Original

charters, writs or indentures remained with their owners and can turn

up anywhere, or nowhere. Court records are scattered around England in

regional record offices, or may even be in private hands. Bodies of material

have gravitated into public archives, but in a random fashion. However,

there are vast numbers of surviving documents relating to property holding.

Their investigation is a genuine historian's detective story.

|

Categories

of Documents Categories

of Documents |

|

|

|

|

|