If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Royal Charters (2) | ||||

| Royal charters did not deal exclusively with grants of land, but could confirm other legal privileges. | ||||

|

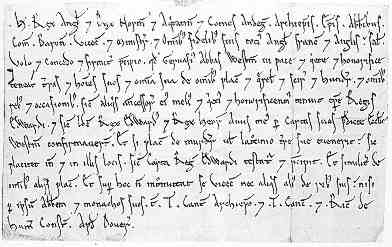

Charter of Henry II, of 1156 (London, Westminster Abbey Muniments no. xliv). (From New Palaeographical Society 1906) | |||

| This document confirms to the abbot of Westminster the right to hold courts in areas where the abbey had possessions without the interference of the sheriff. | ||||

| The above document is set out in similar manner to the previous, with an elaborate salutation that takes up two full lines and a list of witnesses that includes Thomas Becket, then Chancellor of England. The seal is not shown in the photograph, but evidently only fragments are preserved. | ||||

| Royal charters could also be made out to the benefit of individuals rather than religious establishments. | ||||

|

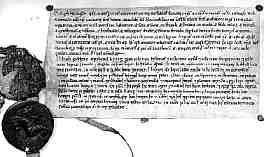

Charter of Richard I, confirming to Alexander de Barentin, butler to Henry II, all his property fairly purchased or confirmed to him by Henry II. (London, Westminster Abbey Muniments no. 657). (From New Palaeographical Society 1906) | |||

| This rather long and detailed charter is produced with elegant calligraphy and has a fine example of the great seal of Richard I, showing the equestrian side in this photograph. No, you can't read it at that magnification, but you can get some sort of idea of just what kind of a splendid object it was. It was not merely a legal document, but a prestigious token with some social significance in its own right. | ||||

| Not all royal charters were necessarily penned in the royal chancery. It was evidently sometimes the practice for some monastic institutions to actually write out the charter for themselves and present it for validation by royal seal. | ||||

|

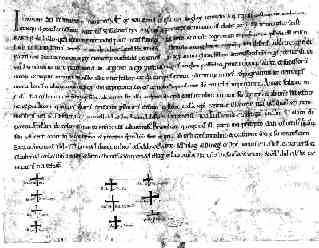

This charter of Henry I (British Library, Campbell Charters xxi 6) confirms to the monks of Christ Church, Canterbury the lands they held in the time of Edward the Confessor and William 1. By permission of the British Library. | |||

| The script of the charter is a protogothic book hand rather than a chancery hand. The monks evidently did not want any misunderstandings over the content, as the text is repeated in Latin and English and the legal clauses include just about every right and privilege in the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary of legal terms. | ||||

| The study of royal charters can give an insight into the development of church and state relations and the privileges enjoyed by the medieval church. There can also be an elucidation of the manner in which the crown asserted its ultimate authority over land ownership. The problem with charters as evidence is that, by their very nature as documents sent out by the crown, they are dispersed all over the country. They were preserved among the documents of private estates or in monastic libraries, from which many have been dispersed or lost. Some have fluttered back into public ownership in local archives or in major institutions like the British Library or the National Archives, formerly the Public Record Office. However, collections may be unsorted and incoherent. | ||||

| Some monasteries and even private individuals kept copies of their charters in cartularies, but there is always some question of authenticity. They may be genuinely medieval, but it was certainly not unknown for monastic scribes to fill in a few gaps in their records with forged documents that they felt ought to be there. This was supposedly more common with cartulary entries, but some forged individual documents are known. | ||||

|

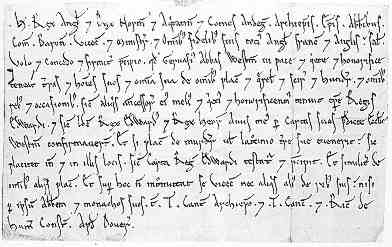

A 12th century forged charter of William II confirming the lands and privileges of Battle Abbey (British Library, Egerton Charter 2211). By permission of the British Library. | |||

| This forged charter even has the names of the witnesses entered with due solemnity, each beside the sign of the cross, and starts with the words IN THE NAME OF THE HOLY AND UNDIVIDED TRINITY. It's almost blasphemy. (See Searle 1968) | ||||

| By the 13th century, copies of charters sent out by the crown were being entered on chancery rolls, and the study of such things becomes a bit more orderly. However, the scattered records of the earlier period document major political and social changes, through the Norman Conquest, through the anarchy of the 12th century and the establishment of more literate systems of government thereafter. | ||||

| The study of the formal structure and wording of documents is known as diplomatic. This seems to be a subject that everybody mentions but nobody knows too much about. Anglo-Saxon scholars have studied these structures in great detail in order to detect the genuine from the forgeries among documents from that time period, but there is evidently no general book on the diplomatic of English charters. Relationships between the wording of documents and their changing social meanings are awaiting the energies of a new generation of scholars with an interest in social history. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||||