If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Breviary (2) | |||

|

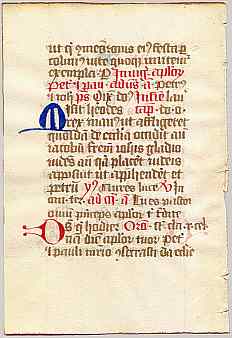

Each of the hours of the divine office is made up of a number of components, which are identified by abbreviated rubrics as shown in the example at left. The psalms and canticles form the basis of each office, canticles beings songs of praise derived from parts of the Bible other than the Book of Psalms. Antiphons are shorter passages, supposedly originating in short chants performed alternately by two choirs. Versicles and responses are short passages chanted by the choir. Hymns are religious poems from a variety of approved sources. Lessons are readings, either from the Bible or the patristic writers. Little chapters are very short readings. Collects are prayers offered towards the end of the office. All this information, comprising parts chanted or read by all the various performers of the ritual, spoken or sung, are coded into the breviary text. The example at left shows how script hierarchies as well as rubrics are used to untangle this complexity, with versicles and responses written in a smaller hand than the other components as an aid to comprehending the structure of the text. As is apparent, there is a large amount of coded information which is only comprehensible to someone fully conversant with the structure of the ritual as a whole. And to think that the practitioners of this art committed vast tracts of this to memory! | ||

| Single column from a page of a 14th century French breviary, from a private collection. | |||

| Other parts of the breviary, as well as the detailed information for each office for all possible seasons, feasts, saints' days and the segments common to all days, included that most essential of items, a calendar. A psalter was also included, generally with the psalms arranged in the order that they were performed in the liturgy rather than their original Biblical order. It also contained certain special offices, of which perhaps the most significant is the Office of the Dead. It could also contain the Office of the Blessed Virgin. This last is the basis for the book of hours, which also includes the Office of the Dead. | |||

|

While this may seem to be an over elaborate text, the performance of the divine office was the major work of the members of enclosed orders, such as the Benedictines in their various branches. Any other work of the day, whether scribing manuscripts, growing cabbages or attending to the administrative work of the monastery, or sleeping for that matter, fitted around this continuous cycle of prayer and praise. The elaborate choir stalls of the great abbeys were not for public display, but were for the eyes of the monks and God. | ||

| The choir of Gloucester Abbey. | |||

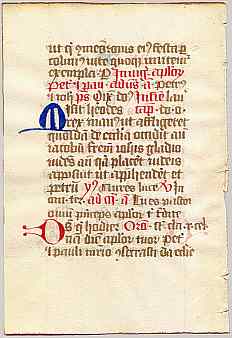

| By the later middle ages there were many clergy and members of non-enclosed orders who were not spending their whole days in choir. The example at right is from a late 15th century breviary, written in a distinctly scruffy Gothic hand, in a single column of fairly large text. The rubric refers to the feast of the apostles Peter and Paul indicating that, unlike a book of hours, it has variants based around the church calendar. Nevertheless, the format does not appear to fit a complete breviary text. There is probably still much to be learned from the study of the many variants of the divine office. |  |

||

| leaf from a breviary with a known date of 1467, from a private collection. | |||

| |

|||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||