If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Why Paleography Sucks (3) | |

| From the 13th century onwards there was a great increase in the quantity of legal and bureaucratic writing. For many purposes writing needed to be carried out rapidly and letters were written joined together, without lifting the pen, or else lifting it but then joining the letters together in simple ways, without little fancy feet and the like. Such scripts are known as cursive, or cursiva if you want to be Latin about it. Some older document paleographers use the term current writing, which becomes currens in Latin. When I went to school we called it running writing, and learning it was a great rite of passage which established you as one of the big kids. | |

| These cursive scripts are immensely variable in general appearance, and the tendency of document paleographers is to classify them pretty broadly, based partly on the shapes of certain key letters and partly simply on where they came from and what they were used for. Even so, the terminology gets messy. From an English perspective, the prototype of cursive document script in the 13th and 14th centuries was called cursiva anglicana. Well, it would be, wouldn't it? It is defined by the particular shapes of a, e, g, r and the short and curly final s. The treatment of other letters, especially those with ascenders, can be very different over time. | |

|

|

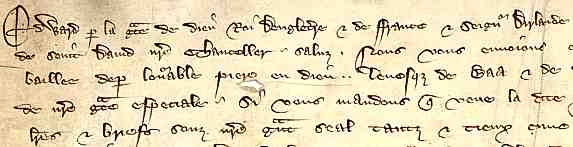

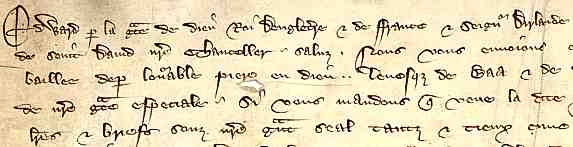

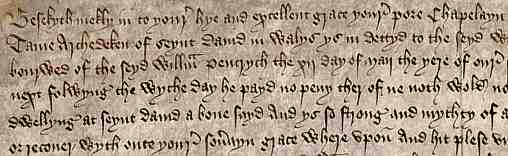

| This is the top left segment of a chancery warrant of 1349, under Edward III, ordering letters and writs under the great seal to the Bishop of Bath and Wells. (London, National Archives C.81/339/20343). By permission of the National Archives. | |

|

|

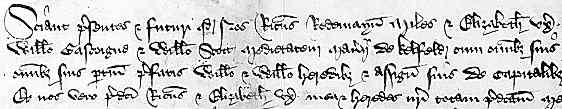

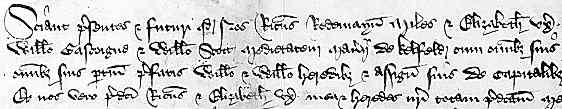

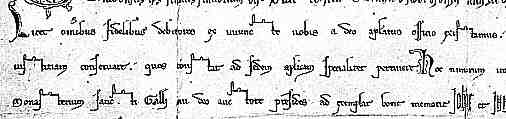

| This is the upper left hand corner of a private charter of Richard Redmayne and Elizabeth, his wife, to William Gascoigne and William Scott, of 1417. The language is Latin (British Library, Harleian Charter 112 C 30). By permission of the British Library. | |

| This is a classification based on form rather than function, as cursiva anglicana also became a book hand. However, it is not based on the general appearance of the writing or generic treatment of certain aspects of general letter forms, but on the characteristics of specific letters. The rather spiky 15th century version shown directly above contrasts markedly in appearance with the loopy 14th century style above it. So even the criteria used for classification are not constant. | |

| In the 14th century a different style of cursive writing rambled across to England from France, having possibly originated in Italy. Writing was going all over the place by this time, as more people were writing and their writings were getting around. English paleographers have called this style Secretary. Dumb name. After all, what do you call a person who writes, however they do it? This also became used as a book hand. It also hybridised with the local cursiva anglicana, and also with angular Gothic book hands to create a range of formal but cursive scripts that, under the influence of the English chancery, was used for books and for documents. | |

|

|

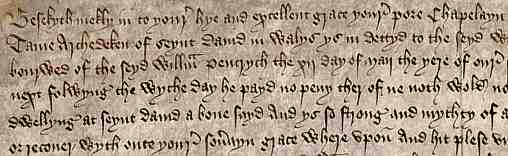

| This sample comes from a petition of 1439 in the National Archives, London (E.28/file59/No.57). By permission of the National Archives. | |

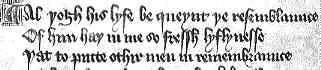

|

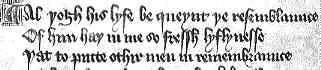

This passage comes from a 15th century copy of Thomas Hoccleve's Regement of Princes, composed around 1412 (British Library, Harley 4866, f.88). By permission of the British Library. |

| Yes, you have looked at the second example already, a couple of pages ago, but if you look at it again you can see the similarities with the document above. If you look very carefully you may note some differences. It's always the way with handwriting. | |

| So what did they decide to call this new phenomenon? At this stage, variants on the word bastard invade the vocabulary: bastarda, Bâtarde, Bastard Secretary. I have always wondered why paleographers considered that these late medieval interactions in handwriting style were illegitimate. Bastard Secretary is particularly problematic, because although it refers to a miscegenated child of French Secretary, the term Secretary was also used for a different style which appeared later in England and was used as a document hand in the late 16th and 17th centuries. As nobody can be the bastard of their own descendants, the classification system wallows into confusion. More recently, paleographers have restored order and dignity to the proceedings by referring to these scripts as hybrida, which is more polite, but possibly no more revelatory. | |

| And that is just England. Cursive scripts were used in documents, and then adapted for books, all over Europe. The local terminology may tell us something of how they were used or perceived in their place of origin, but adds nothing to our comprehension of how they relate to the forms of writing in other places. So in Italy there are cancelleresca and mercantesca, scripts derived from those used for legal and bureaucratic purposes, or from business hands. In the only Spanish paleography book I have been able to get my hands on, dating from 1889, it seems that the succession of scripts used in documents were named from their place of origin (escritura francesca, italica, alemana), from their general form (escritura redonda) and from their function (escritura de privilegios, de albalalaes, de cortesana, procesal). These last refer to various legal hands, which became progressively more untidy and incomprehensible. | |

| The Spanish information came from Muñoz y Rivero, J. 1889 Manual de Paleografia Diplomatica Española de los Siglos XII al XVII which was ferreted out from The Internet Archive. | |

| So there is no real comprehensive classificatory scheme for document hands across the whole of Latin Western Europe or its later vernacular usages. in fact, scholars of historical documents have probably expended more ink and developed more complex schemes of nomenclature for the diplomatic rather than the paleography. This also employs an esoteric vocabulary, most often expressed in Latin, but once again, this is a natural extension of the fact that the documents being studied were, at least in the earlier part of the period, in Latin. The rules for drawing up documents were in Latin to start with. The vocabulary of diplomatic is undoubtedly more consistent than that of paleography, and it's just a bunch of words, so there is no need to be afraid of them. Diplomatic is no more and no less than a description of how a document is constructed, verbally, spatially and stylistically. Paleography comes in there, because certain grades of script may be defined as appropriate for certain grades of document. | |

|

|

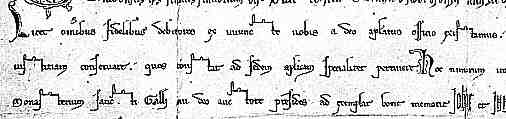

| This segment is from a privilege of Pope Gregory IX of 1234, confirming papal protection to the monastery of St Gall (St Gellen, Stiftsarchiv, A.4.B.3). The script is a formal diplomatic minuscule. (From Steffens 1929) | |

|

|

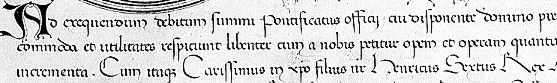

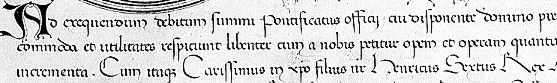

| This is a small section from a papal bull of 1441 of the less formal variety, from Pope Eugenius IV, granting permission to Eton College to lease the lands of the college to best advantage (British Museum, add. charter 15570). (From New Palaeographical Society 1906) | |

| The second of the examples above is in a plainer and less ornamented script than the one above, indicating that is a document of lesser importance. It is much more beautiful. Both scripts would probably be described simply as diplomatic minuscule. | |

| Now let us go back to the early part of our chronology to look at the paleography of book hands. The confusion in the use of terminology here would boggle the mind. | |

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|