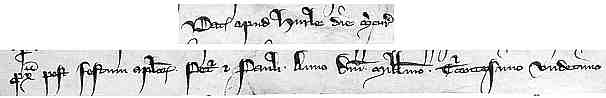

Dat(e) apud Hurle die M(er)cur(ii)

p(ro)x(ima) post festum ap(osto)lor(um) Pet(ri) & Pauli. Anno D(omi)ni Mill(esi)mo T(r)icentisimo vundecimo

Given at Hurley on the first Wednesday after the feast of the apostles Peter and Paul in the year of the Lord one thousand three hundred and eleven (30th June 1311)

The year is no problem, but to work out the day one has to first look up a saints' calendar to discover the date of the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul (29th June) and then consult a perpetual calendar to find out when Wednesdays fell in 1311.

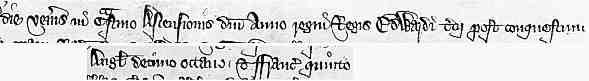

die Ven(er)is in C(ra)stino Ascensionis d(omi)ni Anno regni Regis Edwardii t(er)cii post conquestum

Angl(ie) decimo octauo & Franc(ie) quinto

Friday on the morrow of the Ascension of the Lord in the reign of King Edward the third after the conquest, the eighteenth year of England and the fifth of France (14th May 1344)

This is even more fun, as the feast of the Ascension is tied to the date of Easter, so first you have to look up that for the year, then work out the date of the feast of the Ascension, then use the perpetual calendar to find out when the following Friday was in that year.

There is nothing like conquering France to add a little extra honorific detail to the date. Edward III claimed the throne of France in 1340, undertook to renounce it in 1360 and dropped the double dating, then resumed his claim in 1369, adding the French regnal date in again as if nothing had happened.

An extra dating event is added in the reference to the conquest, that is, the Norman Conquest of 1066. Edward the Confessor was king before the conquest of course, but he doesn't get counted in the conventional numbering of English kings. Using 1066 as a significant starting place for the middle ages in England was actually instigated in the medieval era itself.

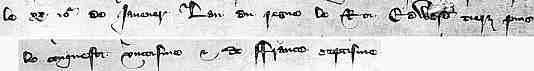

le xx io(ur) Janeuer. Lan du regne le Roi Edward tierz puis

le conquest vintisme & de France septisme

the 20th day of January, the year of the reign of Edward the third since the conquest, fifth and seventh of France (20th January 1347)

That is not a very good translation, but it does seem even in the French to leave a little to the imagination. England doesn't get a mention by name.

in vigilia Natal(is) d(omi)ni Anno regni Regis Henrici q(ua)rti post conquestu(m) p(ri)mo

the day before the Nativity of the Lord in the first year of the reign of King Henry the fourth after the conquest (Christmas Eve, ie. 24th December 1399)

Kings called Henry became numbered in relation to the Norman Conquest as well, even though there weren't any King Henries before the conquest. It had just become one of the honorifics of dating clauses.

the kyng at Kenyngton the xxv day of May the xvii yere of his regne

These were working documents, no doubt originally filed in a logical order, so it does not seem to have been deemed necessary to indicate for posterity exactly whose reign. However, this annotation bears the autograph signature of A. Moleyns who was clerk of the Council for part of the reign of Henry VI and whose signature appears on many documents. That means it has to be 1439.

the xxii day of Juyn

No year is given, not even the regnal year of an unknown monarch. One might surmise that the script has an early 15th century look about it, but paleographical dating can be a dodgy business. However, the assiduous folk at the National Archives have noted that the letters patent referred to in relation to this matter have been entered on the patent rolls, which were kept in nice chronological order. This makes the year 6 Henry V, or 1418.

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).