If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Dealing With Medieval Documents (3) | |

| In reseaching medieval documents, the researcher is not totally dependent upon the survival of the original documents themselves. Many single sheet documents such as charters or important letters were copied into cartularies or registers during the course of the middle ages, so there is a record even if the originals have been lost. How accurate this record may be can be a matter for discussion. Religious institutions were very much involved in maintaining privileges that they had been granted, sometimes from the days before written record when the king made an oral pronouncement on the subject. The cartulary may not have always been a complete record of the legal dealings of an institution, but a compilation of material which served particular purposes. They were also part of the foundation mythology of institutions. Many charters dating from before the 12th century have been found to be forged, or at least written down retrospectively in order to record in writing legal privileges that had been granted, or were said to have been granted, orally. How much easier it must have been to pop in a few early entries to the cartulary to ratify the traditions of the institution. | |

|

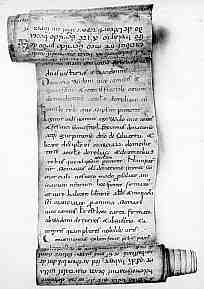

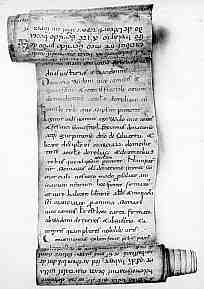

An 11th century cartulary in the form of a roll, of the almshouse of Saint-Martial in Limoges. (Archives hospitalières de Limogers, A 2). From De Boüard 1929) |

| A cartulary in the form of a long roll, like the one illustrated at left, must surely be considered to be a ceremonial object rather than simply a useful piece of recordkeeping. The codex was the more usual form, but they could be elegant objects. Registers of the letters of bishops, abbots or magnates could no doubt also be selective and produced for particular purposes. Still, history would be no fun if there was no argument about the accuracy of the evidence. | |

| Documents were sometimes copied at later dates in cases where they might have some legal significance in family or institutional matters. These copies may survive after the original have become lost. They are secondhand evidence, but they are evidence. | |

|

|

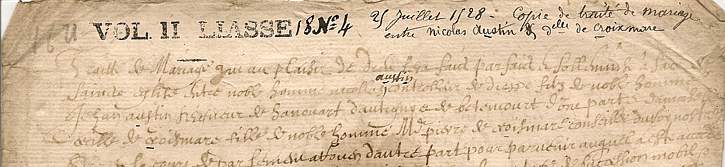

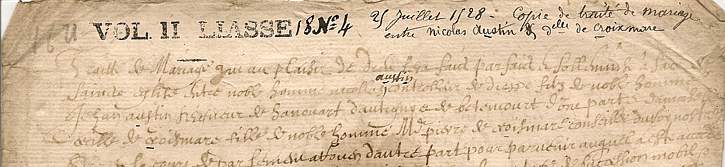

| The beginning of a copy, made in 1621, of a marriage agreement made in 1528, in French, from a private collection. | |

| In the above example, it can only be assumed that there was some sort of family squabble going on about inheritance or one of those other issues that keeps families fighting together, requiring evidence from old legal agreements. I wonder if they sorted it out. | |

| Even if documents no longer survive, there may be evidence that they once existed. | |

|

|

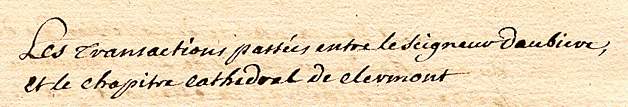

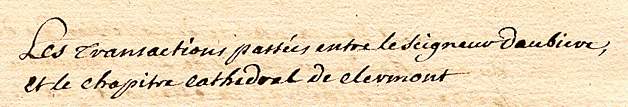

| Heading from a document of unknown date, listing a range of medieval documents relating to relationships between Seigneur Daubiere and the cathedral chapter of Clermont, from a private collection. | |

| The above example represents a list of documents, drawn up at an unknown time but I might be guessing around the 17th century, relating to matters of tithes and the right to nominate prebendaries and dating from 1090 to 1500. Where all those documents are now, who knows? | |

| The previous two examples were presumably drawn up by interested parties to some legal dispute or contemporary matter, but antiquaries of the past have assiduously made copies of old documents out of purely academic interest. This seems to have happened notably in the 17th century, when it seems that there were people who recognised that the world had changed forever and the old world needed to be recorded. It is not uncommon for these copies to have survived after the original documents have been lost. As with any other copies, there must be questions as to the precise accuracy and completeness of the transcripts. Nevertheless, with the tendency of original single sheet documents to disappear one way or another, these transcripts do provide some sort of record of things that once were. | |

| There are many guides to help you with documentary research, and an increasing number of online catalogues. Some are produced by the libraries and archives that hold material. Others are produced by societies dedicated to particular kinds of research. Guides for genealogical research often point to resources which are useful for other historical purposes, and are written so that people who are not already experts in medieval history or law can understand them. Some are indicated in the Links section of this website. It is a good thing to familiarise yourself with this material before you book into an archive. Nothing worse than having somebody plonk something on the desk in front of you and you can't read a thing and don't know where to start. Actually, that happens to everybody at some stage, but with some preparation, the brain will unfreeze and you can make a start. The more material of a particular kind you work on, the more famliar the format and wording becomes, until you are the world's leading expert in some little corner of the documentary universe. | |

|

|

|

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|