If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Single Sheet | |||

| The single sheet was used for a variety of formal documents, as well as for private letters. Parchment was the usual material in the earlier part of the medieval period and right through the era for formal documents. Papyrus charters were produced by the Ravenna chancery after the fall of the Roman Empire and the Merovingian royal chancery used papyrus until the 7th century, while the papal curia retained the tradition until the 11th century. This was evidently a conscious linkage with Roman tradition. Paper became more common towards the end of the middle ages, particularly for private letters. (See Bischoff 1990) |

|

||

|

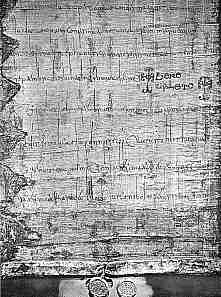

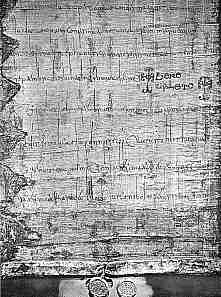

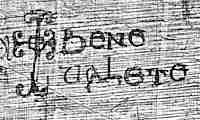

Privilege of Pope Leo IV of AD 850. The damaged document is shown above. At left a detail shows the distinctive texture of papyrus, with its pattern of fibres running vertically and horizontally. (From Steffens 1929) | ||

| Very formal or public documents, such as charters or letters patent, were left open. They were written only on one side. The various royal chanceries, as well as the papal curia, developed extravagant calligraphic scripts for the most significant documents. Private letters or the lower grade of official documents known as letters close were, as the name suggests, closed. These were folded and tied with a thread or parchment strip. | |||

| Formal documents were generally not signed, but were authenticated with a wax seal which was usually attached to the document with a parchment strip. The process of using a seal began in the royal chanceries. In England, the various royal secretariats each had their own version of the royal seal; the great seal, the privy seal and by the 15th century, the signet. (See Elton 1969) | |||

|

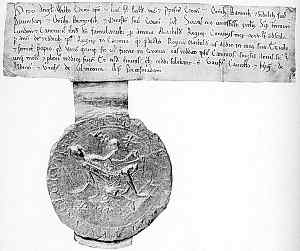

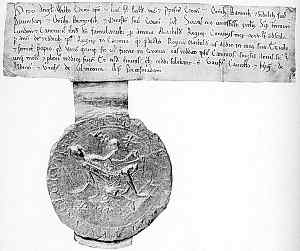

Charter or writ of Henry I, addressed to the bishop of Exeter, the sheriff of Devon and others confirming an annual grant to Holy Trinity, Aldgate, London for the soul of his wife Matilda. (British Library, Cotton Charter vii. 2). (From Warner and Ellis (ed) 1903) | ||

| The above example represents the formal document delivered open. The great seal of Henry I is attached and seems disproportionately large compared to the written parchment. The great seal was double sided and the examples above and below show opposite sides of the same seal. | |||

| The great seal of Henry I on a charter to Christ Church, Canterbury (British Library, Campbell Charter xxi, 6), by permission of the British Library. |  |

||

| Institutional bodies, religious and otherwise, had their official seals. |  |

||

| Replica of the official seal of the Archbishop of York. | |||

| Significant individuals had their own personal seals. |  |

||

| Replica of the personal seal of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury. | |||

| Even relatively insignificant individuals could have their own seal. |  |

||

| Replica of the 12th century seal of Snarre the tollkeeper, discovered in the upper levels of the Jorvik Viking excavation in York. | |||

| The papal curia, as ever, had to be a bit different to everybody else. While the usual seal was of wax, papal documents were authenticated with a lead seal, or bulla, giving rise to the term papal bull. |  |

||

| Detail of the lead seals of the papal privilege of Pope Leo IV shown above. (From Steffens 1929) | |||

| When a sealed document is referred to, this does not mean that it was sealed up, but that it had a seal attached. It could be an open document, although seals were also used on closed documents or letters, not only to authenticate them, but to ensure that they were not opened before they reached their intended recipient. | |||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||