If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| The Codex | ||

| A codex is a book. It's that simple. A pile of pages, generally written on both sides, held together by a binding. What else could there possibly be to say? | ||

|

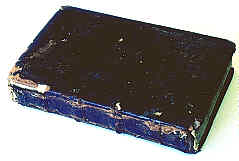

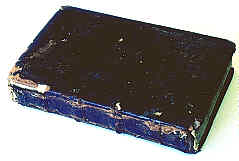

A late medieval codex in its original binding, a 15th century volume of the works of Cicero, by permission of the University of Tasmania Library. | |

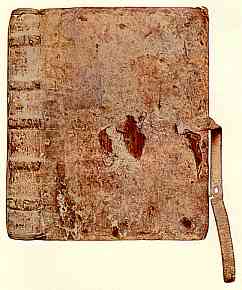

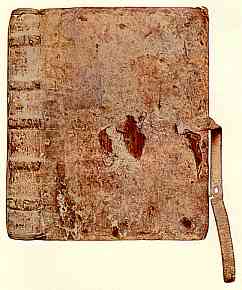

| In the medieval era, the bindings were generally of leather, sometimes decorated, wrapped around boards and laced together across the spine. The ridges over the lacings are visible in the examples above and to the right. A fastening strap was commonly included. |

|

|

| Medieval binding of the Reading Abbey cartulary (British Library, Egerton 3031). | ||

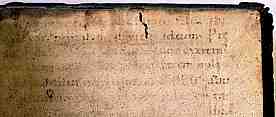

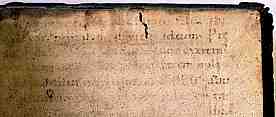

| In the earlier part of the medieval era the pages were of parchment or vellum; expensive but very durable. From around the 13th century, paper steadily became more common, particularly for books which were not of the most luxurious grade. Cheaper paper books brought books to more people. Inside the bindings the leather covering was glued down with sheets of parchment known as pastedowns. Sometimes these have been cannibalised from earlier manuscripts, and such little surprises appear even into the era of printed books. | ||

|

This parchment pastedown, from the binding illustrated at the top of the page, still bears 12th century writing. By permission of the University of Tasmania Archives. | |

|

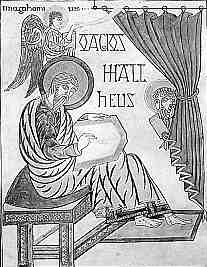

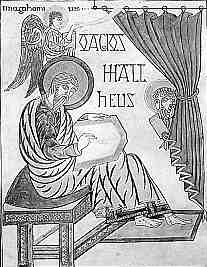

This famous miniature of St Matthew shows him writing into an already bound codex, but this was generally not how it was done. That this is more fanciful than literal is indicated that the good man is not shown with the other equipment of a scribe, usually carefully depicted in later medieval miniatures: writing desk, ink horn, knife and sometimes rulers. | |

| The evangelist Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, Cotton Nero D IV, f.25b). (From E.G. Millar 1923 The Lindisfarne Gospels London: British Museum) | ||

| If you are browsing through the paleography or book production section of your library and start looking at the detailed descriptions of medieval manuscript books, you may fine a section entitiled codicology, followed by a most esoteric series of code and jargon. What is this all about? | ||

| The Medieval Manuscript Manual website provides information on the Structure of the Text in a medieval book, as well as some of the technicalities of book construction in its Bookbinding section. Or take a look at Cornell University's The Evolution of the Medieval Book exhibition, particularly the Leather and Chains section. Truly! | ||

| Codicology is the study of the structure of books; not their content, handwriting or decorative style, but simply the way they have been put together. The examination of these things can allow investigation of various avenues. It can help with dating the manuscript. It can allow the researcher to determine whether the manuscript is, in fact, complete or whether parts are missing. It can be used in relation to studies on the production and distribution of works. The code of codicology is based on the way in which books were made and assembled. it is best cracked by looking at some real examples. | ||

|

|

||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||