|

|

Miniatures |

|

The

pictures, either full page or smaller, found in manuscript

books are referred to as miniatures.

This is not because they are particularly small. The term derives from

the Latin minium, meaning red lead, with

which the pictures were initially drawn. However, compared to painting

in other media, they are small, so the term has acquired a resonance which

diverges from its strict etymology. Manuscript miniatures are the most

prolifically surviving examples of medieval art and some are of the most

elegant quality. The study of miniatures is a branch of art history in

its own right. They have been extensively illustrated and written about.

Schools of painting and individual artists have been identified. |

|

In

the earlier part of the medieval period, the scribe

of a manuscript was also sometimes the illustrator, as evidenced by inscriptions

and colophons. |

|

Later,

when the production of books became more commercialised, the miniaturist became

a specialised job. This was the final stage of completion of a book, with

the painter working under instruction to place the miniatures in the spaces

assigned, with the content decided by the bookseller and client in consultation.

Even the finest artist worked under orders. No wild creative flights of fantasy

here. The genius had to be in the detail. There are numerous manuscripts extant

with unfinished miniatures, where the process was never finally completed. |

|

Not

all manuscript miniatures were the brightly coloured and gilded productions

so beloved of beautiful modern picture books. In some cases outline drawings

actually represented the finished product. |

|

|

The

intricately drawn miniatures of the 11th century Harley Psalter (British

Library, Harley 603), a copy of a 9th century Carolingian work, were executed

as coloured line drawings. By permission of the British Library. |

|

As

with historiated

initials, the content of miniatures related to the text. They thus

served as placemarkers in the text and identified the beginnings of particularly

significant passages. In the case of liturgical works, they could serve as a mnemonic for the remembering of such passages

and they also created a spiritual space and environment. They do not just

illustrate the book, they are part of the spiritual power of the book

which itself is a sacred object as well as a medium for recording sequences

of words. |

|

Above,

as is usual, a 15th century book of hours displays a miniature of a funerary

mass at the beginning of the section containing the vigils of the dead (National

Library of Australia, MS 1097/9, f.86r), by permission of the National Library

of Australia.

At

right, the small kneeling figure of a canon reads the office for the dead

from an enormous book at the feet of the funerary effigy of the founder of

the Augustinian house of St Barthlomew, Smithfield London. |

|

|

This

concept of the miniature as an aid to spirituality and devotion rather

than as a text illustration is evidenced in the standard scheme of decoration

of the book of

hours. Each office in the section containing the hours of the Virgin

generally begins with a miniature which does not directly illustrate the

text. In the most common scheme it illustrates episodes from the life

of the Virgin and the nativity. An alternative scheme uses scenes from

the passion of Christ. These do not relate literally to the words on the

page, but are aids to contemplation of holy concepts associated with the

Virgin Mary. |

|

|

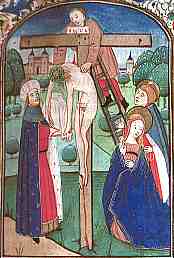

In

a 15th century book of hours (National Library of Australia, MS 1097/9,

f.48r) the section on vespers of the hours of the Virgin begins with a

miniature of the deposition from the cross, with the Virigin kneeling

at the foot. By permission of the National Library of Australia. |

|

Sometimes there was more than just mental contemplation involved. The book of hours tided the devout reader through life's troubles, and the images in it were regarded as efficacious as direct conduits to Christ, the Virgin Mary or the saints. Images were clutched or kissed in times of strife. The little miniature on the left of Christ's face on Veronica's handkerchief is seriously smudged and I suspect we are looking at the results of somebody's ancient travails. Veronica's handkerchief, according to Christian legend but not Biblical authority, was used to wipe the suffering face of Christ during the Passion, and is therefore highly symbolic for the relief of suffering. |

| Miniature of St Veronica's handkerchief on a page from a 15th century French book of hours, from a private collection. |

|

|

|

|

continued |

Decoration Decoration |

|

|

|

|