|

|

|

Initials

and Borders |

|

|

The

production of decorative initials and borders in manuscript

books became steadily more prolific as the middle ages progressed. Such

decorations undoubtedly added prestige to a volume and to some extent

can be seen as simply having been done for swank. They also have a function

in the reading of the text, just as a chapter heading does in a modern

book.

|

|

|

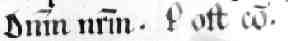

The

simplest, earliest and most persistent form of differentiated heading

was known as rubric,

the name deriving from the fact that it was executed in red. Rubrics were

used for headings for sections of text, serving as simple location markers.

In books of ritual such as the missal,

breviary or even

the book of hours,

rubrics were used to differentiate instructions, or markers of the progress

of the ritual, from the actual text being read or performed.

|

|

|

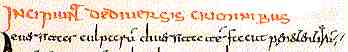

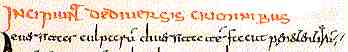

Rubric

indicating a chapter heading in an 8th century collection of patristic

works (Cologne Cathedral Library, MS XCI). |

|

|

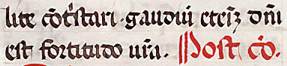

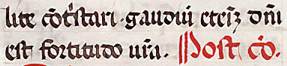

In liturgical books, rubrics can indicate the stage of proceedings, as in these two examples from missals where the words post co, for post communio, indicate the words to be recited after the act of communion. |

|

|

The example above left is from a 12th century missal

(British Library, add ms 16949, f.iv), by permission of the British Library.

And yes, the photograph is black and white, but it is a rubric. The living colour example below is from a a page from a 15th century missal, probably French, from a private collection. |

|

|

|

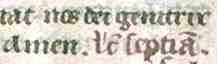

|

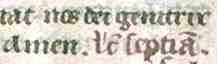

A

rubric indicates the stage of the ritual in a 15th century book of hours,

by permission of the University of Tasmania Library. |

|

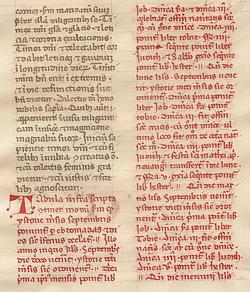

| Rubrics were not necessarily just brief headings. Books like the breviary contained complicated instructions for the conduct of the divine office on all the days, both ordinary and festive, of the year. These could be extensive. On the example at left, the rubric instructions take up the better part of the written area of the page, and they continue on the other side. Perhaps they are not really decorative at all, but should be considered as utility. However, every from of decorative writing in a medieval manuscript book performs some function, even when it is also designed to be very beautiful. |

|

|

| Leaf from a late 15th century Augustinian breviary, use of Rome, from a private collection. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

the commercial production of books in the later middle ages, the rubricator

was a specialised position. As well as adding headings, they also sometimes

interpolated corrections to the text. In the later medieval period these

small headings, such as the chapter headings of the Bible,

were sometimes produced in other colours, notably blue. |

|

|

Chapter heading in red and blue from a 13th century miniature Bible, from a private collection. |

|

|

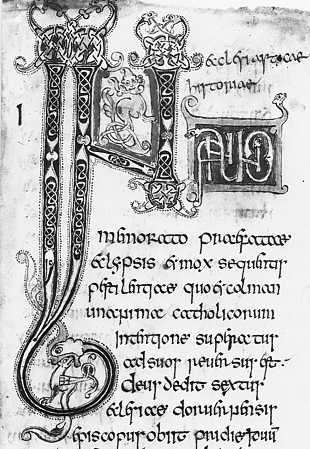

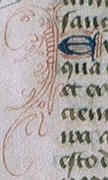

Decorative

initials and headings are regularly found in prestige works. As well as

adding social value to the volume, they also serve as placemarkers for

the text. Certain styles of decoration are diagnostic of time and place,

so that examination of these details can be used for sourcing and provenancing

works. Intricate swirling and interlacing designs with beasties swallowing each other, typical of Anglo-Saxon art, are found on this decorative initial. |

|

|

|

Initial in a

9th century copy of the works of Bede (British Library, Cotton Tiberius

CII, f.94), by permission of the British Library. |

|

|

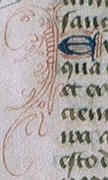

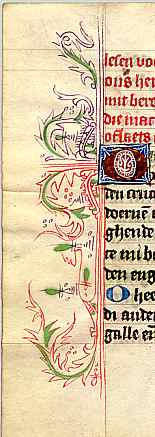

At left, an

initial is surrounded by spidery and intricate late Gothic decoration

on a leaf from a late 15th century book of hours, by permission of the

University of Tasmania Library. At right, a decorative Gothic initial from a 15th century Dutch book of hours, from a private collection. |

|

|

| The use of intricate coloured penwork around decorative initials is characteristic of the Gothic era. The multicoloured penwork on the example at right is evidently characteristic of certain workshops in Haarlem in the Netherlands; and yes, the text is in Dutch. Eras and geographical regions had their own recognisable particularities in the production of decorative initials. They are a study in their own right. |

|

|

|

|

| The

use of gold in initials and line fillers added to the prestige of a volume,

although it was common in even modest books of hours in the late medieval

period. Gold leaf

was rolled out immensely thin. The area to which it was to be applied was

built up with a layer of gesso, the gold leaf glued to it and carefully

burnished (with a beaver's tooth according to some traditions). The appearance

is of a thick, glowing mass of gold, but it is all an optical illusion.

Strictly, the term illumination

applies only to manuscripts decorated with gold in this way, as the pages

were regarded as glowing with their own light. |

|

|

Gold

leaf applied to an initial and to a decorative line filler in a page from

a late 15th century French book of hours, by permission of the University

of Tasmania. |

|

|

|

|

Large

decorative headings might serve to introduce a section of text and act

as a place marker, but sometimes it seems that the expectation was that

the text itself was well known and remembered, as decorative effects could

render legibility difficult. Some Anglo-Saxon and early Irish manuscripts

displayed headings that were like a puzzle or anagram. |

|

|

|

|

The

heading for Psalm 26 in the 8th century Vespasian Psalter (British Library,

Cotton Vespasian A1 f.31), by permission of the British Library. |

|

| The example above reads DNS (DOMINUS) INLUMINATIO MEA. The letters are entangled into a puzzle knot. |

|

|

continued  |

|

Decoration Decoration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|